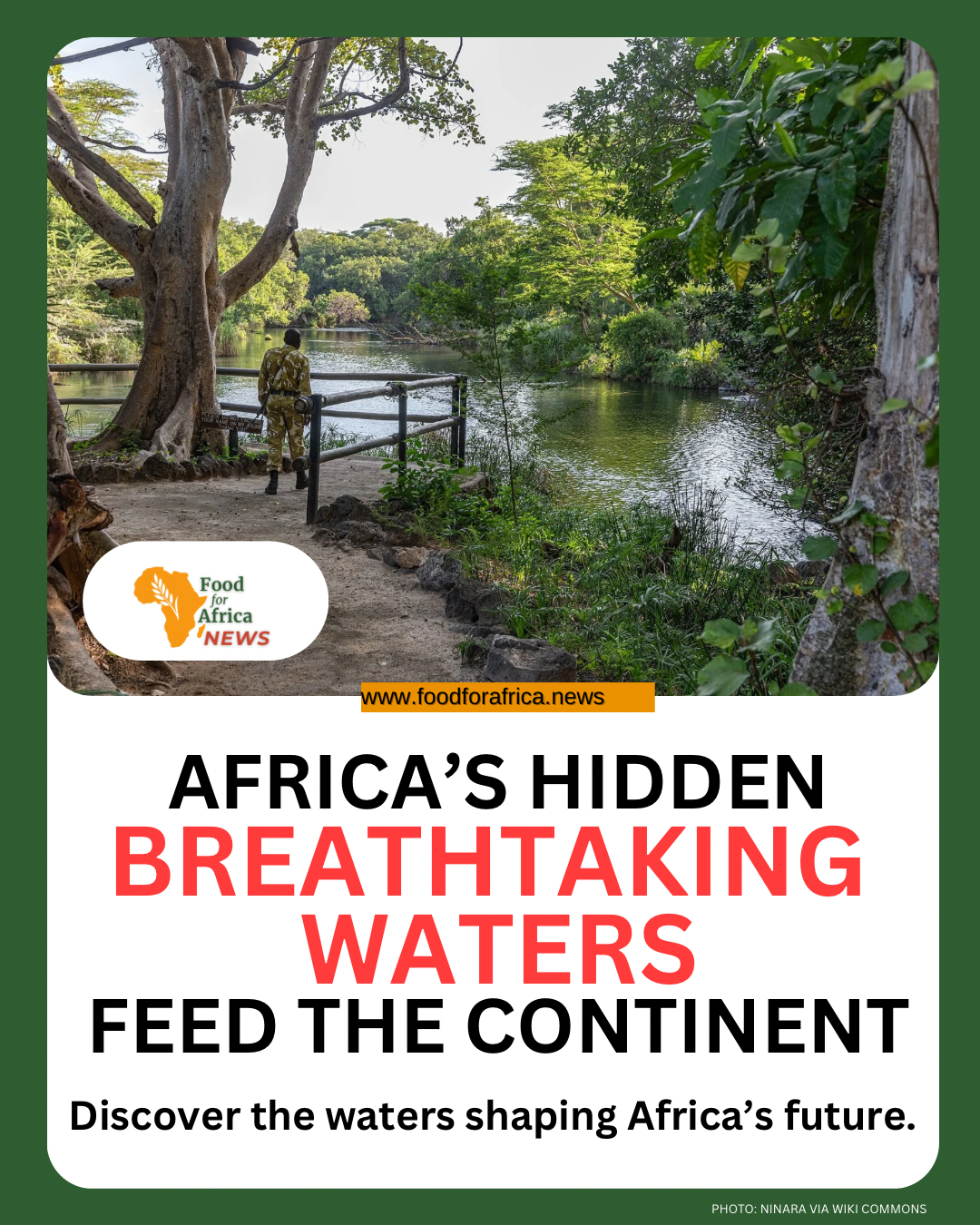

Across Africa, some of the most striking water sources sit far from tourist routes. They appear in salt pans, forest valleys, deep river channels, and mist-covered belts. To visitors they look unusual. To nearby communities they are part of daily survival. These waters keep fields alive, move food to markets, and support families through seasons that are becoming less predictable.

Here are five water sources that are as beautiful as they are useful.

Senegal coastline

Lake Retba

Photo attribution: https://edwardasare.com/a-look-at-lake-retba-senegals-pink-lake/

Many people know Lake Retba for its pink color. The shade changes across the day and pulls the eye immediately. Around the shore, the scene is more practical. Workers pull up boats loaded with salt and stack it in long drying rows.

Roughly 3,000 people earn their income from this lake. In a typical year it produces about 60,000 tonnes of salt, and a large share is used to preserve fish. The preserved fish moves inland, where cold storage is limited and salt remains essential. What looks like an unusual lake surface helps keep food available for households far from the coast.

Southern Kenya

Mzima Springs

Photo: Wlenjo, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mzima Springs begins underground, moving quietly through old volcanic rock before it reaches open pools. When the water surfaces, it is clear and steady even in severe heat.

The spring system releases more than 300,000 cubic metres of water a day. Part of that flow feeds communities and small farms near Tsavo. Families use it for vegetables, fruit trees, and mixed household plots. In a region that can lose crops within days of high heat, this volume of consistent water makes a direct difference.

…………………………………………………………

Central Africa

The Congo River

Photo: The Congo River near Kisangani, bay MONUSCO/Myriam Asmani, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Congo River is deep enough in some areas to appear almost black. It is one of the most important transport routes in Central Africa and supports many of the communities along its banks.

The wider basin holds about 30 percent of Africa’s freshwater and supports more than 70 million people. Canoes and small cargo boats move cassava, plantains, dried fish, maize, and basic goods between villages and trading centres. For many of these communities, there is no workable road alternative. The river is the link that keeps food moving.

Eastern and Ashanti Ghana

Forest waterfalls, Kintampo Falls and stream systems

Photo: Kintampo Waterfalls, by Knowledge and philosophy, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In Ghana, many farmers rely on smaller water sources that sit inside forest areas or run between farms. In Eastern and Ashanti, narrow streams support cocoa, cassava, plantain and vegetable plots. In Bono East, Kintampo Waterfalls feeds the Pumpum River, which then breaks into smaller channels used by nearby communities.

These waters are not large, but they hold steady when rains shift. Cocoa alone involves more than 800,000 smallholder farm families across the country, and most depend on rainfall rather than formal irrigation. Streams linked to Kintampo and similar sources help farmers bridge short dry spells and keep young crops alive. They are simple systems with a direct role in production, even if they rarely appear in national reports.

Southern Africa

Victoria Falls mist belt

Photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Victoria Falls is well known, but the mist belt around it receives far less attention. The spray creates a humid strip that cools the air and changes the soil conditions downwind.

Across the larger Zambezi Basin, more than 5 million hectares of land are under cultivation, with about 183,000 hectares equipped for irrigation. Many of these plots belong to smallholders farming under 2.5 hectares. In the mist belt, pockets of moisture allow families to grow vegetables and small crops that do not do well in nearby drier fields. The falls attract visitors, but the conditions they create support quiet, steady food production.

The quiet work behind the beauty

These water sources were not engineered. They developed naturally, and communities built their food systems around them. Their beauty draws attention, but their value lies in the work they do each day.

As pressure on water increases, protecting these places matters not only for scenery but for the fields, markets, and families that rely on them.

Thank you for featuring this