The real killer is not the animal: it is the lack of safe water.

At sunrise on Lake Victoria, women kneel at the shoreline with plastic containers while fishing canoes slide past them into the mist. By nightfall, one of those same people may not return home. Not because of crime. Not because of war. But because they needed water.

The hippopotamus kills more people than lions and elephants combined. Across large parts of Africa, survival and death still share the same water. The animal takes the blame. The system most responsible is broken infrastructure. So what is the real killer?

In many river and lakeside communities across East and Southern Africa, water does not come from a tap. It is carried home on heads and backs from open water. Families wash in the same rivers where they drink. Fishermen work in narrow canoes inches above hippo territory. Farmers plant crops at the very edge of rivers because that is where the soil still holds moisture.

Photo: Amuzujoe, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hippos defend these waters with force. When humans enter, whether by boat, bucket, or bare feet, they are seen as a threat. The collision is deadly. People know the risk, but they have no choice when the water system does not function properly. This is survival in places where no alternative exists.

Imagine stepping into a river you have used your entire life. You know there is danger in the water, but the greater danger is having no water at all to meet life’s basic needs. You are forced to choose between the risk of a hippo attack and daily survival. So you choose. And you do not see danger. You see drinking water. You see food. You see survival. Below the surface, a three ton animal is submerged with only its eyes above water. Hippopotamuses often spend the day hidden beneath the surface. When a woman steps forward with a jug and bends toward the water, the hippo does not flee. It charges upward.

Survivors of such attacks have described being lifted out of the water by the animal’s mouth. Boats split in half. People thrown like objects. Some are crushed instantly. Others are dragged under and drowned. For many river communities, these waters are their kitchen, bathroom, road, and workplace. The danger is constant.

Across Africa, wildlife agencies, conservation groups, and medical researchers frequently cite an estimate that up to five hundred people are killed by hippopotamus attacks each year. Experts also agree this number is almost certainly underreported, because many rural deaths never reach hospitals or official records.

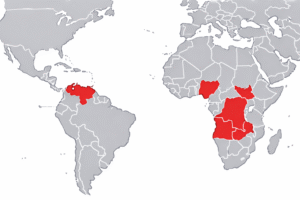

The highest fatality clusters repeatedly appear around the Lake Victoria Basin in Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya, the Zambezi River system in Zambia and Mozambique, Lake Malawi and surrounding river settlements, and river communities in parts of West Africa including Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Photo: Lake Victoria in Tanzania, N17RM, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In these zones, open water remains the primary source for drinking, bathing, laundry, fishing, and transport. People do not enter once. They enter again and again, every single day.

Hippos also live in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, and protected areas of Kenya. Yet mass fatality patterns do not appear there. The reason is simple. People no longer rely on rivers for daily survival.

In those regions, homes have piped or borehole water. Fishing operates from regulated raised landing points. Riverbank farming is separated from the waterline. Wildlife patrols track hippo movement near settlements. Hippos remain dangerous but the forced daily human intrusion into their territory disappears. Death rates fall sharply where water becomes optional, not compulsory.

A full grown hippopotamus weighs more than one and a half tons. It can outrun a human over short distances on land and move silently in water. Its jaw strength is strong enough to crush a canoe, snap limbs, and shatter bone in a single motion. Its lower tusks can grow longer than a human forearm.

Hippos kill by crushing boats and flipping them, dragging victims underwater to drown, biting through the torso or limbs, and trampling those who fall in farming zones at night. Medical case studies from East and Central Africa show survivors often lose arms or legs or suffer permanent nerve damage and deep infection. Many never return to work.

Photo: Kenya, Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Imagine paddling at dusk on the Zambezi River. The surface looks calm. Suddenly your kayak is launched into the air. A hippo rises from beneath you. Within seconds, your companion is pulled under and killed. That happened near Victoria Falls. One man survived. One man did not.

In another recent case on a southern African river, a tourist was grabbed mid canoe, thrown into the air, bitten repeatedly across the body, and left with massive internal injuries. He survived only because of rapid emergency evacuation. Thousands of similar attacks never make headlines. They end in local funerals.

The most effective way to stop these deaths is not killing animals. It providing water systems where communities have access to boreholes, hand pump wells, piped standpipes, raised washing platforms, and basic village storage systems. This removes people from dangerous water and hippo attacks drop because there is less daily human traffic.

Photo: Charlie.Smatt, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Until full infrastructure reaches every village, survival depends on behavioral choices. Most fatal attacks happen in when it is dark, while alone and by surprise. The absence of buffer zones between crops and the shoreline is deadly.

Hippos are not predators of humans. They are territorial animals defending ancient water routes. The real threat is a development failure that forces entire populations into exposed water every day.

Where water systems exist, deaths fall. Where they do not, funerals continue.

This is why the hippopotamus became Africa’s deadliest animal. Not because it hunts humans. But because broken water systems leave humans with no choice.

Sources

Featured photo: Joachim Huber, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Africa Check

Yes, hippos kill around 500 people a year in Africa. Fact check and explanation of underreporting.

https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/meta-programme-fact-checks/yes-hippos-kill-around-500-people-year-africa

BBC Wildlife Magazine, Discover Wildlife

Deadliest animals to humans, comparing hippos, lions, elephants and others.

https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/deadliest-animals-to-humans

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Hippopotamus overview, territorial behavior, danger to humans.

https://www.britannica.com/animal/hippopotamus-mammal

A Z Animals

Hippo attacks, how they kill, attack patterns, danger to boats and people.

https://a-z-animals.com/animals/hippopotamus/hippo-attacks-how-dangerous-are-they-to-humans

The Wild Source

Why hippo death estimates vary, underreporting, and attack behavior.

https://thewildsource.com/should-you-fear-hippos-on-safari-debunking-the-deadly-hippo-myth

Wikipedia

1996 Zambezi River hippopotamus attack, Zimbabwe.

Documented fatal attack and survivor Paul Templer case.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1996_Zambezi_River_hippopotamus_attack

The Guardian, September 2024

British tourist narrowly survives hippopotamus attack on the Kafue River in Zambia.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/sep/26/british-tourist-narrowly-survives-hippo-attack-zambia

University of Leeds

Hippos and human conflict in Africa, data gaps and research.

https://environment.leeds.ac.uk/see/news/article/5459/hippos-and-human-conflict-in-africa