How a working cat can save a season of food

At night, when the cooking fires cool and the streets settle, the real work begins. Rats move fast in the dark. They smell grain from far away. A single rat can tear through a sack of rice in one night. A family can wake up to damage they cannot afford.

In many West African homes, the first line of defense is not a metal door or a locked room. It is a cat.

Worldwide, rodents contribute to roughly 280 million cases of undernutrition and expose about 400 million people each year to rodent-borne diseases. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, rodents account for a median crop loss of 16 percent in the field and 8 percent in storage.

Rodents can destroy massive amounts of stored grain in some rural areas when pest control is weak. One working cat can protect an entire household’s food supply through the season.

Across cities, towns, and villages, cats live quietly beside families. They sleep on sacks of maize. They stretch across rice bags. They slip through kitchens and storage rooms without drawing attention. Most people do not call them pets. They call them part of the house.

Their job is simple. Keep the rats away.

A good cat can protect months of food. Rice meant to stretch through the dry season. Flour set aside little by little. Groundnuts saved from week to week for market day. Rodents do not only eat food. They spoil it. They tear bags and spread disease. When rats get into storage, the loss can be devastating.

Photo: Yintan, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This is why many households say, half joking and half serious, that the cat earns its keep.

You find them under cooking tables. On shelves near grain. Curled up beside sacks that hold everything a family has saved. They eat scraps. Bones. What the household can spare. In return, they stand guard through the night.

A woman once explained why she fed her cat before feeding herself. “If the cat sleeps, we lose the rice,” she said. In homes without electricity, without sealed storage rooms, without refrigerators, the cat becomes the cold chain. The security system. The last protection between food and hunger.

Children learn early that the cat is not a toy. It has work to do, and it settles into that role easily. Over time, it becomes part of the family as a working animal. When a good cat is lost, the loss shows up in the kitchen as well as in the home.

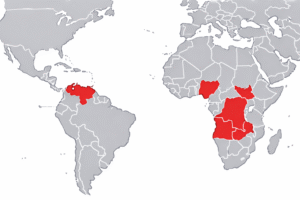

This quiet role plays out across West Africa. In Ghana, cats sleep on top of sacks of rice in family compounds. In parts of Nigeria, market women feed cats that stay near their grain stalls because the cats keep the rats away. In Senegal, cats move freely through homes, mosques, and food markets, protected by both custom and faith.

In rural areas of Mali and Niger, cats guard mud granaries filled with millet and sorghum. Without them, rodent loss can wipe out weeks of food in days.

You will not find this written neatly in any ledger. But you see it the moment a house loses its cat and the rats come back.

Still, the story is not perfect everywhere.

In some regions, cats face danger. Fear, superstition, and misunderstanding lead to neglect or poisoning. In others, rodent poison meant for rats kills cats as well. And when the cats disappear, the rodents do not wait. Food loss follows quickly. People feel it within weeks.

The truth is simple. Where cats are protected, food protection improves. Where cats are harmed, food insecurity grows quietly behind the scenes.

The good news is that this is changing.

Across cities and towns, attitudes are shifting. Young people share photos of their cats. Markets protect the animals that guard their stalls. Veterinarians and rescue groups are teaching safer rodent control and basic care. Even small changes are saving animals and keeping food in homes.

Cats will never appear in agriculture budgets. They will never feature in food security speeches. They will never receive funding.

But tonight, across West Africa, they will still be awake. Watching the grain. Guarding the rice. Protecting the meal that has not yet been cooked.

And in many homes, hunger will not win because a cat is on duty.

Sources

- Featured photo: Prasan Shrestha, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Frontiers: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/agronomy/articles/10.3389/fagro.2022.936908/

- Natural Resources Institute (NRI). Postharvest Loss Reduction Interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Experiences and Perspectives. 2024. https://www.grtd.fcdo.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Food-loss-postharvest-landscape-report.pdf GRTD

- Shukla, Namita; Tripathi, AK; Sharma, Kranti; Tiwari, Ashutosh. “Rodent management in grain storage facilities.” International Journal of Research in Agronomy 8(2): 40–46 (2025). https://www.agronomyjournals.com/2025/8(2)/2572/2572.htm ResearchGate

- Donga, TK; et al. “Rodents in agriculture and public health in Malawi.” Frontiers in Agronomy 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/agronomy/articles/10.3389/fagro.2022.936908/full Frontiers

- Swanepoel, LH; Swanepoel, CM; Brown, PR; Eiseb, SJ; Goodman, SM; et al. “A systematic review of rodent pest research in Afro-Malagasy small-holder farming systems.” PLOS ONE 12(3): e0174554 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174554 PLOS

- Stathers, Tanya; Holcroft, Deirdre; Engelbert, Mark; Ravat, Zafeer; Marion, Pierre. “The evidence on crop postharvest loss reduction interventions for sub-Saharan African and South Asian food systems: a 2024 systematic scoping review update.” 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2025.102727 ScienceDirect

- Mawoneke, KG; et al. “From farm to fork: a review of strategies for sustainable reduction of post-harvest losses in Sub-Saharan Africa.” 2025. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311932.2025.2588851 Taylor & Francis Online