When hunger is widespread, can animal ethics realistically come first?

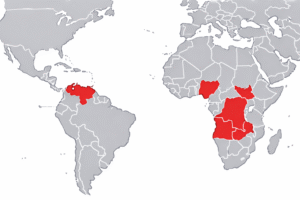

Animal rights often come second when hunger is widespread. In communities where food is uncertain, survival shapes every decision, including how farming is practiced. Ethics are not dismissed, but they are delayed. This trade-off is not unique to Africa, but its effects are more visible where malnutrition remains widespread. Across much of the continent, animal welfare laws are limited, unevenly enforced, or focused primarily on disease control, veterinary standards, and trade rather than rights. From the outside, this is often described as neglect. On the ground, the explanation is simpler: hunger shapes policy, and feeding people comes first. But, is there a way that ethics can come first?

In regions where food insecurity is widespread, animals are treated primarily as assets. Livestock provides calories, income, and a buffer against uncertainty. In these conditions, animal use is rarely debated as an ethical issue. It is a survival strategy.

This reality does not mean animal exploitation is inevitable. It means ethical outcomes in food systems are closely tied to whether people have viable alternatives.

For decades, livestock has been promoted as a solution to hunger, particularly in rural Africa. Yet animal-based food systems are among the most resource-intensive ways to produce nutrition. Livestock requires large amounts of land and water and is highly vulnerable to climate stress. Droughts, rising feed prices, and disease outbreaks routinely destabilize animal-dependent households, leaving both people and animals exposed.

Malnutrition across Africa is also frequently mischaracterized. Lack of protein and calories typically misconstrued as the key problem; however an underreported issue is the widespread deficiency in essential micronutrients such as iron, vitamin A, iodine, zinc, and B-complex vitamins. These deficiencies drive stunting, weakened immune systems, maternal health complications, and impaired cognitive development. Increasing meat production does not reliably address these gaps, particularly where animal products are consumed infrequently or are priced beyond reach.

Plant-based foods already dominate daily diets across the continent. Staples such as rice, maize, cassava, sorghum, legumes, and vegetables form the foundation of food consumption in West Africa and beyond. The challenge is not cultural resistance to plant-based diets, but limited access to nutrient diversity, fortification, and nutrition education.

Public health research has long shown that improving nutrition outcomes does not require a major expansion of animal agriculture. Strategies such as micronutrient fortification, crop diversification, improved seed access, and better food preparation practices can significantly reduce malnutrition at lower cost and with greater resilience to climate shocks.

Flavor and preparation also matter. Nutrition interventions often fail when food is unappealing or unfamiliar. Local cooking practices, spices, and taste preferences strongly influence whether healthier foods are adopted. Addressing hunger is not only a question of nutrients, but of how food fits into daily life.

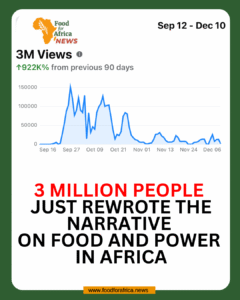

Information plays a similar role. Education and media shape how communities understand nutrition, health, and food choices. In many cases, behavior changes follow awareness and trust more than policy directives.

This context has direct implications for animal protection. In regions where animals are used because alternatives are limited, ethical change is unlikely to come from regulation alone. When plant-based food systems become more affordable, reliable, and nutritionally effective, reliance on animals declines naturally. Ethics follow access.

Africa’s food future will be decided less by moral arguments and more by practical solutions that work under pressure. Addressing hunger through sustainable, plant-based options is not only a public health strategy. It is one of the most realistic pathways toward reducing animal exploitation in food systems shaped by survival. If hunger were to no longer dictates every choice, what kind of ethics could Africa’s food systems afford to embrace?

SOURCES

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Rome: FAO, 2023. https://www.fao.org/publications/sofi

World Health Organization (WHO). Micronutrient Deficiencies. Geneva: WHO, updated 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/micronutrients

UNICEF. Malnutrition in Children. New York: UNICEF, 2023. https://www.unicef.org/nutrition

FAO. Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options. Rome: FAO, 2006. https://www.fao.org/3/a0701e/a0701e.pdf

FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture – Trends and Challenges. Rome: FAO, 2017. https://www.fao.org/3/i6583e/i6583e.pdf

World Bank. Repositioning Nutrition as Central to Development. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2006. https://documents.worldbank.org

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Global Nutrition Report 2022. Washington, DC: IFPRI, 2022. https://globalnutritionreport.org

FAO and WHO. Guidelines on Food Fortification with Micronutrients. Geneva: WHO, 2006. https://www.who.int/publications