U.S. sanctions in Africa are usually described as targeted. Officials stress that they are aimed at specific individuals, armed groups, or entities accused of corruption, human rights abuses, or destabilizing entire regions. They are not presented as punishment of populations. In practice, the effects rarely remain contained.

Across Africa, sanctions consistently extend beyond their stated scope. They move through banking systems, trade finance, shipping insurance, and currency access. Long before they reach political elites, they affect civilians.

Targeted on paper, expansive in effect

No African country today is under a full U.S. trade embargo comparable to Cuba or Iran. Most sanctions affecting African states are administered through the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control and are officially classified as targeted measures. That distinction matters in law. It matters far less in finance.

Banks evaluate sanctions on risk. Penalties for missteps are severe and compliance costs are high. The safest decision is often withdrawal.

Correspondent banks exit markets. Letters of credit are delayed or refused. Even permitted transactions become slow, expensive, or impossible to execute. Over compliance becomes standard practice.

This response is not written into sanctions statutes. It is an outcome of how global finance protects itself. The result is a financial freeze that extends well beyond any individual designation.

When money slows, food follows

Food trade depends on financing. Imports rely on credit, insurance, shipping guarantees, and access to foreign currency. When sanctions are announced, banks reassess entire jurisdictions, not just named actors. Insurance premiums rise. Shipping rates increase. Importers cut volumes. Exporters wait months for payment. Prices rise without shortages ever being declared.

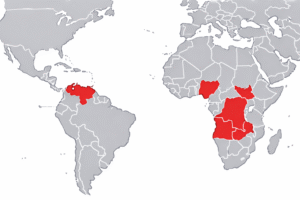

This pattern has repeated in countries affected by conflict related sanctions, including Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, and Somalia. Neighboring countries often feel secondary effects through shared ports, trade corridors, and banking relationships.

By the time food prices increase, the original policy objective is no longer part of the conversation.

Sanctions increase hunger risk

According to United Nations agencies, more than 280 million people across Africa are undernourished, roughly one fifth of the continent’s population. Over 60 million children are affected by stunting or wasting, conditions directly linked to chronic malnutrition.

These figures rise most sharply in contexts marked by conflict, financial isolation, and disrupted trade. Sanctions do not cause drought or war. But they intensify vulnerability by weakening currencies, restricting food imports, and reducing household purchasing power at moments when economies are at their weakest.

The World Food Programme has repeatedly warned that financial restrictions and sanctions related over compliance increase hunger risk, particularly in countries dependent on imported staples. When financing tightens, diets narrow. Protein becomes scarce. Nutrient rich foods disappear. Calories remain, but nutrition declines. This is how sanctions show themselves towards the most vulnerable.

Malnutrition in early childhood leads to permanent consequences, including impaired cognitive development which affects the ability to receive proper education. This corresponds to reduced lifetime earnings. This has a lifetime affect, extending far beyond if and when sanctions are lifted.

Unfortunately, these outcomes are rarely included in sanctions assessments.

Who absorbs the pressure?

Sanctions frameworks assume pressure applied at the top will force behavioral change. What they often ignore is how economic pressure is distributed. While political elites and armies adapt quickly, with systematic advantages, civilians often cannot.

Small traders lose access to banking. Farmers struggle to import inputs. Informal markets shrink. Households skip meals or remove children from school. Women often reduce their own food intake first.

The burden concentrates among the urban poor, displaced populations, and women led households. Sanctions rarely land where they are aimed.

Africa is rarely embargoed, but often excluded

Africa is not cut off because it is comprehensively sanctioned. It is cut off because engagement is treated as optional. Once sanctions enter a risk calculation, nuance disappears. Banks choose safety. Corporations choose predictability. Aid organizations struggle to move funds. Diaspora remittances slow.

These effects are not announced and therefore not debated. The population absorbs the effects.

The unresolved question

Do sanctions change behavior at the top faster than they erode life at the bottom? For many households, the answer does not come through policy reform. It arrives as a higher food bill, a delayed shipment, or a transaction that never clears.

Sanctions are written for governments. They are paid for by civilians.

Sources

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Rome: FAO, 2023.

World Food Programme. Global Report on Food Crises 2024. Rome: WFP, 2024.

UNICEF, World Health Organization, and World Bank Group. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition. New York: UNICEF, 2023.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. “Sanctions Programs and Country Information.” Office of Foreign Assets Control. Accessed 2025. https://ofac.treasury.gov.

World Food Programme. “Over-Compliance and Humanitarian Access.” Policy Brief. Rome: WFP, 2022.

International Monetary Fund. Trade Finance and Global Food Security. Washington, DC: IMF, 2022.

Council on Foreign Relations. “Understanding Sanctions and Their Economic Effects.” CFR Backgrounder. New York, 2023.