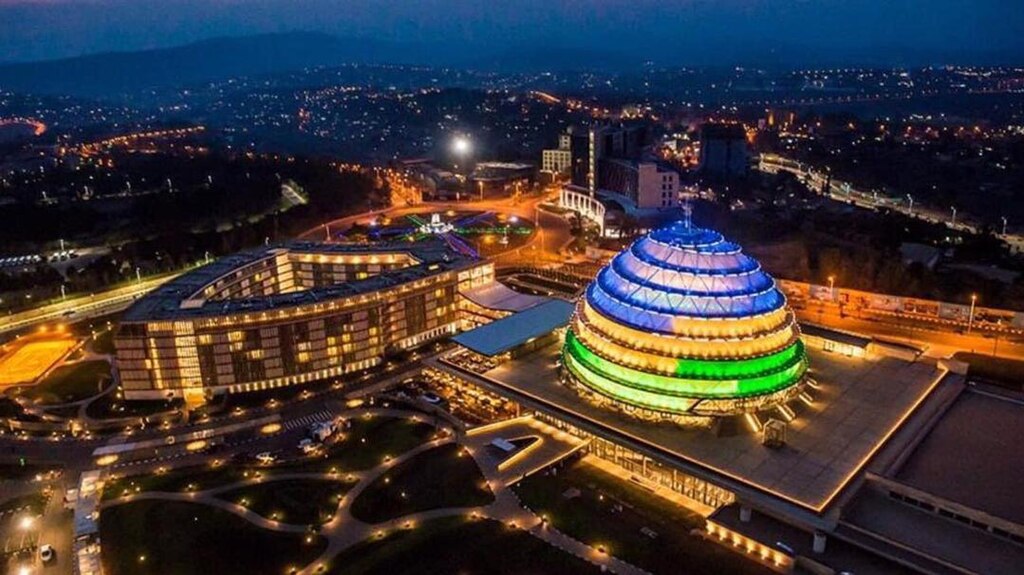

FFA News – Africa Is Rising, Episode 1

After the 1994 genocide, Rwanda’s state institutions were left in disarray. Government offices, public records and administrative networks were either destroyed or abandoned. Rebuilding required basic systems that could operate every day, not temporary campaigns or emergency directives. The approach that followed focused on routine administration, consistent record-keeping and services delivered on a predictable schedule.

Rwanda has one of the youngest populations in the region, with an average age of 22. Young people are increasingly present in public institutions: the National Youth Council operates in every district, and youth representatives sit in local councils and Parliament, including seats reserved for youth at the national level. More than 60 percent of public service entrants each year are under 35. Access to digital government services and entrepreneurship programs has also expanded, allowing young adults to start businesses, apply for training and engage in decision-making processes at earlier ages than in previous generations.

Fabos ishimwe, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Planning systems are now aligned across districts. Reports move through one chain of responsibility, and public offices open on regular schedules in both rural and urban areas. Stability is maintained through daily administration rather than one-time directives.

Digital platforms support routine procedures. Land titles, ID cards and business registration can be processed without personal intermediaries. Records are traceable and procedures are clearer than before.

Most households farm small terraced plots for food and income. When land records are reliable, clinics are nearby and markets function consistently, families can plan for the next season instead of reacting to uncertainty. This connection between administration and daily work is one of the foundations of Rwanda’s recovery.

Photo: johncooke, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Healthcare is a central part of the system. Rwanda’s community-based health insurance program, Mutuelle de Santé, covers an estimated 86 percent of households. Premiums are scaled by income. This reduces out-of-pocket medical costs and allows clinics to plan budgets more consistently. Households are less likely to delay treatment due to financial uncertainty.

The health network includes more than 500 health centers and over 1,400 health posts. Approximately 45,000 community health workers operate inside the communities they serve. They monitor pregnancies, check child growth and refer medical cases to clinics when needed.

In Nyagatare District, a mother brought her child to a community health worker after noticing weight loss following illness. The child was referred to a nearby clinic for treatment and nutritional support. The family paid the standard insurance contribution. Without this system, the household may have needed to sell livestock or seek informal loans.

Child stunting has declined over the past two decades, from nearly half of children to about one-third. The figure remains high. Current efforts aim to increase dietary diversity. As incomes rise and markets stabilize, more households are including vegetables, fruits and proteins alongside staple grains.

Conditions vary across the continent. In South Sudan, conflict and displacement continue to interrupt basic services. Facilities may stand, but staffing and supply routes are inconsistent. Administrative stability is still being established in those areas.

Administrative capacity depends on records that are kept, responsibilities clearly assigned and services delivered on schedule. These are practical habits that develop over time. They are being built in many local contexts across Africa at different speeds.

State operations differ by country. Some have stable routines in place. Others are building them while managing conflict or climate pressures. The pace of development is uneven, as it has been in most regions undergoing institutional rebuilding.

Rwanda’s experience shows that functioning systems are not the result of speeches or symbolic reforms. They form in the ordinary details of daily governance: offices that open when posted, documents processed without delay and basic services maintained even in difficult conditions. Rwanda did not wait for external guidance or uniform consensus. It built the routines that allow a state to function.

Sources

Rwanda Ministry of Health — Health Facilities and Community Health Overview

https://moh.gov.rw/

Mutuelle de Santé (Community-Based Health Insurance) Summary — Rwanda Ministry of Health

https://moh.gov.rw/index.php?id=31

World Bank — Rwanda Health System Support and Coverage Data

https://data.worldbank.org/country/rwanda

WHO Rwanda Country Profile — Health System and Outcomes Data

https://www.who.int/countries/rwa/

UNICEF Rwanda — Child Nutrition and Stunting Trends

https://www.unicef.org/rwanda/nutrition

CDC — Rwanda Health System Strengthening and Community Health Worker Program

https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/countries/rwanda/default.htm