Nigeria is facing one of its most serious hunger and malnutrition crises in years, raising difficult questions about where political and international priorities truly lie.

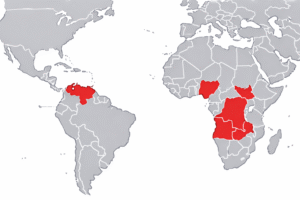

Current food security projections estimate that around 30.6 million Nigerians could face acute food and nutrition insecurity during the June–August 2025 lean season. Conflict, inflation, climate shocks, and displacement continue to drive the increase. Northwestern states such as Zamfara, Sokoto, and Katsina remain among the most affected, while the northeast, including Borno and Yobe, continues to record high levels of food insecurity.

At the same time, emergency food assistance is shrinking. The World Food Programme has warned that life-saving food distributions in parts of northeast Nigeria have been suspended due to funding gaps, even as needs continue to rise. Aid agencies report that existing resources are no longer enough to meet demand.

Malnutrition remains a major concern, particularly among children. Estimates from UNICEF indicate that about two million Nigerian children suffer from severe acute malnutrition, placing Nigeria among the countries with the highest child malnutrition rates globally. Long-term effects, including stunting and developmental delays, remain widespread.

Photo: Jane Miller/DFID, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

These pressures are unfolding alongside ongoing insecurity. Nigeria continues to battle armed groups across several regions, and recent U.S.–backed airstrikes targeting Islamic State-linked militants in Sokoto State point to deepening military cooperation between Abuja and international partners.

But as security operations intensify, many analysts argue that hunger itself has become a security issue. Conflict disrupts farming, displaces communities, and fractures food supply chains, deepening poverty and creating conditions that fuel further instability.

This leaves an unresolved debate: should security responses dominate policy, or should food security, nutrition, and agricultural resilience be treated as equal priorities? Critics say funding for military efforts often overshadows investment in rural livelihoods, emergency feeding, and long-term food system recovery. Others argue that stability is impossible without first addressing the basic needs of vulnerable populations.

With Nigeria projected to have one of the largest food-insecure populations in Africa, the hunger crisis is no longer a side issue. It is a political, economic, and humanitarian challenge that will require sustained attention beyond short-term security responses.

Sources

United Nations World Food Programme (WFP). Nigeria Emergency Dashboard and Food Security Updates. Rome: World Food Programme, 2024–2025.

https://www.wfp.org/countries/nigeria

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Nigeria: Humanitarian Needs Overview 2024. New York: United Nations, 2024.

https://www.unocha.org/nigeria

UNICEF. Severe Acute Malnutrition in Nigeria: Situation Reports. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2024.

https://www.unicef.org/nigeria

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Cadre Harmonisé Analysis: Nigeria. Rome: FAO, 2024.

https://www.fao.org

Reuters. “U.S.-Backed Airstrikes Target Islamist Militants in Northwest Nigeria.” Reuters, 2024.

https://www.reuters.com

International Crisis Group. Violence, Food Insecurity, and Rural Livelihoods in Nigeria. Brussels: International Crisis Group, 2024.

https://www.crisisgroup.org

World Bank. Nigeria Poverty and Food Inflation Brief. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2024.

https://www.worldbank.org/nigeria