Inside a Northern Ghana study on food insecurity and mental health

“Go away,” Kosi mumbles. Her classmates inch their chairs back, creating space. A few giggles ripple across the room. Kosi keeps her eyes down. She takes deliberate bites of her rice, chewing each mouthful twice before swallowing.

She did not eat breakfast. Dinner will be scarce, if it comes at all. The effort of interacting with her peers feels heavy. She is irritable and drained. At the end of the day, Kosi cycles home barefoot, alone.

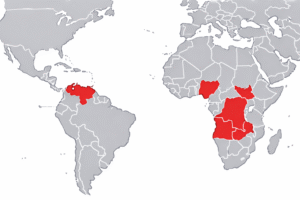

Firedupformore, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Over time, Kosi has lost confidence. Stress and embarrassment follow her through the school day, closely tied to her family’s poverty. She avoids eye contact. She keeps to herself. At times, she quietly questions her place in the world. Kosi is not alone.

Research from Northern Ghana suggests that experiences like hers reflect a broader and measurable pattern linking household food insecurity with mental health risk among adolescent girls.

What the study found

A 2023 study published in BMJ Nutrition, Prevention and Health examined the relationship between household food insecurity and depressive symptoms among girls aged 10 to 17 in the Mion District of Ghana’s Northern Region. The researchers surveyed households and assessed mental health indicators using validated screening tools.

The findings were stark. More than 70 percent of participating households were classified as food insecure. About one in five adolescent girls met the criteria for likely depression. Girls living in moderately and severely food insecure households had significantly higher odds of depressive symptoms compared with those from food secure households, even after adjusting for socioeconomic and health related factors.

Photo: Mac-Gbathy, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The authors are careful in their conclusions. The study does not claim that food insecurity directly causes depression. Instead, it identifies a graded association. As food insecurity increases, so does the likelihood of depressive symptoms.

That distinction matters.

Hunger beyond calories

Food insecurity is often discussed as a lack of calories. In practice, it frequently involves limited dietary diversity and inconsistent access to nutrient dense foods. In Northern Ghana, diets may rely heavily on staples when resources are scarce, with fewer fruits, vegetables, and protein rich foods.

While the BMJ study focuses on food insecurity rather than specific nutrients, existing nutrition research links deficiencies in iron, iodine, zinc, and B vitamins to fatigue, reduced concentration, and mood related symptoms. For adolescent girls, whose nutritional needs increase during growth and menstruation, these gaps can be particularly consequential.

Researchers emphasize that the social pathways are as important as the biological ones. Chronic worry about meals, reduced energy at school, and the social stigma of poverty can combine to strain mental well being during adolescence, a critical period for emotional development.

The weight of silence and stigma

Mental health challenges among adolescents in Ghana often remain hidden. Multiple Ghana based studies on mental health stigma describe widespread fear of labeling, social exclusion, and misunderstanding around mental illness. These attitudes can discourage young people and families from seeking help, even when distress is evident.

For girls in food insecure households, this silence can deepen isolation. Emotional withdrawal, irritability, and declining school engagement may be misread as behavioral problems rather than signals of distress shaped by structural conditions.

The result is a cycle where need goes unaddressed.

A public health issue, not a personal failure

The Northern Ghana study contributes to a growing body of evidence that adolescent mental health cannot be separated from material conditions. Depression risk in this context is not best understood as an individual weakness or a cultural issue. It is linked to uncertainty, scarcity, and sustained stress within the household.

The findings also point toward prevention. Interventions that stabilize food access, improve dietary quality, and reduce household stress may offer mental health benefits alongside nutritional ones. School feeding programs, income smoothing initiatives, and community based support systems may play a protective role, particularly for girls.

Kosi’s quiet withdrawal in the classroom is not an isolated story. It is part of a wider pattern that data now helps make visible.

Understanding that pattern is a first step toward addressing it.

Source

BMJ Nutrition, Prevention and Health (2023). “Household food insecurity and depressive symptoms among adolescent girls in Northern Ghana.”

https://nutrition.bmj.com/content/6/1/56

Disclosure: Kosi is a composite drawn from real life experiences. Identifying details and names have been changed to protect privacy. Photos are for illustration purposes.