The European Union is increasingly framing its Africa minerals strategy as development aid. The argument is familiar: large infrastructure projects inject capital, create jobs, raise export revenues, and over time reduce poverty.

That timeline does not match the reality of hunger.

Across West Africa, poverty is not experienced as a future growth problem. It is experienced as empty meals, volatile food prices, and food systems that fail long before mineral revenues reach ordinary households.

Yes, mineral corridors can stimulate growth; but at what pace and where exactly where the growth be? Will growth be fast enough, and broad enough while not widening the gap between rich and poor?

Growth Versus Survival

Europe’s minerals push, under frameworks such as Global Gateway, reflects a rational concern about supply security for copper, cobalt, and other critical inputs. Funding for these projects is increasingly justified as partnerships that will pump money into local economies.

Extractive growth models, however, tend to concentrate early gains among a narrow group: large firms, political elites, and skilled workers clustered around export infrastructure.

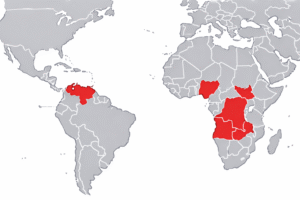

Photo: Shahir Chundra, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Food systems behave differently.

Investments in agriculture, logistics, and electricity place money immediately into the hands of farmers, transporters, warehouse workers, processors, traders, and market sellers. That income circulates locally within weeks, not years. Hunger declines at the same time economic activity increases.

The economic returns are simply faster and broader when food systems are funded first.

Hunger Is Not a Production Problem

Throughout parts of Africa, food insecurity persists despite substantial agricultural activity. The issue is not that food is not grown. The issue is that food does not move efficiently, does not store safely, and does not reach consumers at prices they can afford.

Large volumes of locally produced food are lost after harvest due to inadequate storage, weak cold chain, poor feeder roads, and fragmented transport networks. At the same time, logistics and transport costs inflate the final price of staples, placing food out of reach for low income households.

These dynamics are visible today in markets. When food prices rise, families reduce meals, switch to less nutritious diets, or pull children out of school. Hunger becomes a structural poverty trap rather than a temporary shock.

Photo: Alex Proimos from Sydney, Australia, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Money Exists. The Allocation Is the Choice.

The EU has committed to mobilizing up to €150 billion for Africa through Global Gateway. These funds are already being deployed at scale for transport corridors designed to move minerals efficiently from inland regions to ports.

If even a modest share of that investment were paired with food system infrastructure, the impact would be immediate.

Redirecting or matching:

- 5 percent would equal roughly €7.5 billion

- 10 percent would equal roughly €15 billion

At that scale, Ghana and Sierra Leone could see transformative upgrades in storage, aggregation, transport, processing, and regional food trade.

Food systems are not a side project. They are infrastructure.

What a Food Corridor Looks Like in West Africa

A food corridor does not replace extraction infrastructure. It runs alongside it.

In Ghana, this means modern storage near production zones, aggregation hubs connected to Accra and Kumasi, and reliable power for milling and processing. Reduced spoilage and lower transport costs translate directly into lower food prices.

In Sierra Leone, food corridors link ports, regional markets, and inland production with storage and processing capacity that reduces dependence on emergency imports and stabilizes seasonal shortages.

Food corridors focus on:

- Storage that prevents post harvest loss

- Predictable transport that stabilizes prices

- Regional trade efficiency that moves food where it is needed

- Local processing that keeps value in country

Each element creates jobs while reducing hunger at the same time.

Electricity and Hospitals: Hunger Shows Up in Clinics First

Hunger is not only a food issue. It is a health systems issue.

In both Ghana and Sierra Leone, hospitals treat the consequences of malnutrition without having reliable nutrition supply chains. Maternal malnutrition, child wasting, and diet related illness increase healthcare costs and weaken the labor force.

Investing in hospital linked nutrition systems reduces admissions, shortens recovery times, and improves long term productivity. Reliable electricity makes this possible, powering cold storage, food preparation, and basic medical nutrition.

These are preventative investments with immediate returns.

Faster Growth, Lower Risk

Mineral corridors may raise GDP. Hunger quietly erodes it.

Chronic malnutrition reduces labor productivity, raises healthcare costs, and undermines educational outcomes. Asking populations to endure years of hunger while waiting for extractive growth to trickle down is not a neutral policy choice.

Food systems investment addresses hunger immediately while still stimulating economic activity, with broader participation and lower inequality risk.

A Question Policymakers Rarely Ask

If Europe accepts that minerals are strategic enough to justify billions in upfront investment, why is food, which determines survival, stability, and productivity, still expected to wait?

Sources

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction. Rome: FAO, 2019. https://www.fao.org/interactive/state-of-food-agriculture/2019/en/. FAOHome

World Bank. Missing Food: The Case of Postharvest Grain Losses in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2011. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/820211468005693818/missing-food-the-case-of-postharvest-grain-losses-in-sub-saharan-africa. World Bank

European Commission. “EU-Africa: Global Gateway Investment Package.” Brussels: European Commission International Partnerships, accessed 2025. https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/policies/global-gateway/initiatives-sub-saharan-africa/eu-africa-global-gateway-investment-package_en. International Partnerships

European Commission. Global Gateway. Brussels: European Commission International Partnerships, accessed 2025. https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/policies/global-gateway_en. International Partnerships

African Development Bank Group. Feed Africa Strategy 2016–2025. Abidjan: African Development Bank Group. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Policy-Documents/Feed_Africa-Strategy-En.pdf. African Development Bank

Reuters. “Nearly 55 Million People Face Hunger in West and Central Africa.” Reuters, April 12, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nearly-55-million-people-face-hunger-west-central-africa-2024-04-12. Reuters

Associated Press. “UN Report Reveals Alarming Rise in Africa’s Food Insecurity.” AP News, 2025. https://apnews.com/article/0d366a4042d4524a79cb5b47a94bc0cd.