How a crop introduced centuries ago became a backbone of food security and why farmers still face deep challenges.

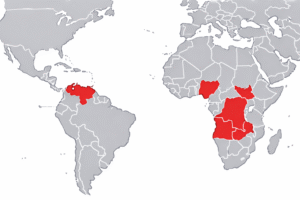

Cassava did not originate in West Africa. It was carried from South America through early trade and colonial networks and found a home in parts of the continent where few other crops survived. Its ability to thrive in poor soils, tolerate irregular rainfall, and be harvested over a wide window made it a reliable fallback for families facing seasonal hunger and agricultural instability. Over generations, cassava moved from a crop of necessity to the foundation of many farm households’ diets and rural economies.

Today, cassava is among the most widely grown and consumed staple crops in West Africa. The region accounts for a significant share of Africa’s production, feeding millions even when prices of imported cereals surge and other staples fail to produce due to drought or poor soils. But this dominance masks structural gaps: the crop’s low nutrition content, limited market integration, and persistent challenges for smallholder producers mean that reliability does not always translate into resilience.

Cassava on West African Farms

Cassava (Manihot esculenta) is a root crop valued primarily for its high carbohydrate content and adaptability. In 2022, global cassava production reached more than 330 million tonnes, with Africa accounting for over 60 percent of that total; Nigeria alone produced nearly 60 million tonnes, representing a substantial portion of West Africa’s cassava output. Wikipedia+1

West Africa produced over half of Africa’s cassava in recent evaluations, with the crop cultivated across nearly all countries in the region. It is a staple food — and often a full day’s supply of calories — for many rural families, particularly in areas where rainfall and soil fertility are unreliable. westafricaconnect.com

Smallholder farmers dominate cassava production, typically growing it alongside other traditional staples. Cassava’s ability to withstand drought and poor soils makes it attractive for households that cannot afford irrigation or costly inputs such as fertilizer. FAOHome

Strengths of Cassava as a Crop

What sets cassava apart is not its nutrition — it is starch-rich but low in protein and micronutrients — but its resilience and consistency. Cassava continues to produce food even when maize or rice fail, providing a buffer against famine and lean seasons. Its wide harvesting window allows roots to remain in the ground until needed, reducing risk for farmers who cannot afford to lose a crop. Wikipedia

These traits underpin cassava’s role as a crisis crop: when food systems are stressed, cassava becomes a household lifeline. Its roots can be processed into various forms — such as gari or fufu — that are widely consumed across markets and communities. westafricaconnect.com

Challenges Beyond the Field

Despite its importance, cassava farming is often synonymous with subsistence rather than prosperity. Yields per hectare in much of Africa remain below global averages, constrained by limited access to improved planting materials, soil fertility challenges, and a lack of extension services that could increase productivity.

Once harvested, cassava roots spoil quickly without processing, forcing many farmers to sell at low prices or lose part of their crop. Processing equipment and storage infrastructure are scarce in many rural areas, reducing opportunities for value addition and market engagement.

Nutrition is another limitation. While cassava roots provide energy in the form of carbohydrates, they are low in essential vitamins and protein — a gap that diets relying heavily on cassava struggle to fill. In some communities, cassava leaves are eaten and provide additional nutrients, but this is not universal and does not fully offset the root’s low micronutrient content.

Women and Cassava Processing

Women play a central role in cassava processing. From peeling and fermenting to milling and market sales, their labor transforms the raw root into staples such as gari, fufu, and cassava flour that support household food security and generate income. These activities often serve as a vital source of cash for basic needs, including school fees and medical expenses. Anecdotal reports from markets and communities highlight the collective nature of processing, where women’s cooperatives share equipment and knowledge to improve efficiency and earnings.

Yet even this positive economic role is not without strain: limited access to mechanized mills and fluctuating prices for processed products keep many women processors in low-margin activities. Despite their critical function in food systems, women often lack access to credit, training, and markets that could expand their economic impact.

Cassava in Daily Life and Culture

Cassava is more than a field crop: it is embedded in regional foodways and daily meals. Gari, a dried and granulated form of cassava, appears in breakfast bowls and street food. Fufu, a pounded staple, accompanies stews and sauces. Market days center on cassava products alongside yams, plantains, and grains. These foods connect households to centuries of culinary tradition while serving practical nutrition needs.

Cassava’s resilience makes it indispensable to West African food security. It keeps people fed when other options fail and anchors rural livelihoods. At the same time, its limitations — low nutritional density, lack of market value, and processing bottlenecks — underscore that food security is more than calories alone.

Understanding cassava’s role means acknowledging both its strengths and its gaps. For communities and policymakers alike, supporting cassava farmers with better inputs, processing access, and diverse crop integration could make this ancient staple even more central to sustained food and nutrition security.

Sources

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, The Cassava Transformation in Africa (FAO, 2025), accessed December 2025, https://www.fao.org/4/a0154e/a0154e02.htm. FAOHome

Cassava production data, Cassava, Wikipedia, last edited 2025, accessed December 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cassava. Wikipedia

Nigeria cassava production, Agriculture in Nigeria, Wikipedia, accessed December 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_Nigeria. Wikipedia

West Africa cassava production overview, Cassava Value Chain – ECOWAS Competitiveness Programme (West Africa Connect, 2022), accessed December 2025, https://westafricaconnect.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Cassava-ECOWAS-Investment-brochure-EN.pdf. westafricaconnect.com

Nutrients and role of cassava, A. W. Borku et al., “Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz): its nutritional and food security potential,” Springer Encyclopedia Article (2025), accessed December 2025, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43621-025-00996-2. SpringerLink

Y. Guo et al., Closing Yield Gap of Cassava for Food Security in West Africa, Nature Food (2020), accessed via abstract December 2025, https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-020-0107-9.

Featured image: Emmanuel Ssekaggo, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons