A slow-moving hunger crisis is unfolding across the Horn of Africa, where households lose strength long before the world calls it a famine.

In Turkana, northern Kenya, children walk dry riverbeds in search of water. Wells have dropped to mud, and the ground offers little to eat. Families lose strength long before the world calls it a famine. This crisis does not break suddenly. It advances one missed meal at a time.

Across the region, land that once fed entire villages now produces almost nothing. Grazing land has thinned, and fields stand bare. Some areas are facing the worst drought seen in forty years. The hunger and thirst that follow is slow and exhausting. It wears people down one day at a time.

Farmers describe planting season as a risk they no longer feel they can take. Seeds cost more than before and water is difficult to secure. Livestock deaths have become common, sometimes happening faster than herds can recover. A farm that once supported a household now struggles to feed even one person. In many homes, meals have been reduced to a single serving a day.

Nearly 23 million people in the region are experiencing extreme hunger. This is not because there is no food in the world. Global markets are full and stable. The issue is access. The areas where hunger is most severe are also the areas with the least infrastructure, the weakest roads, and the greatest distance from aid delivery and government support.

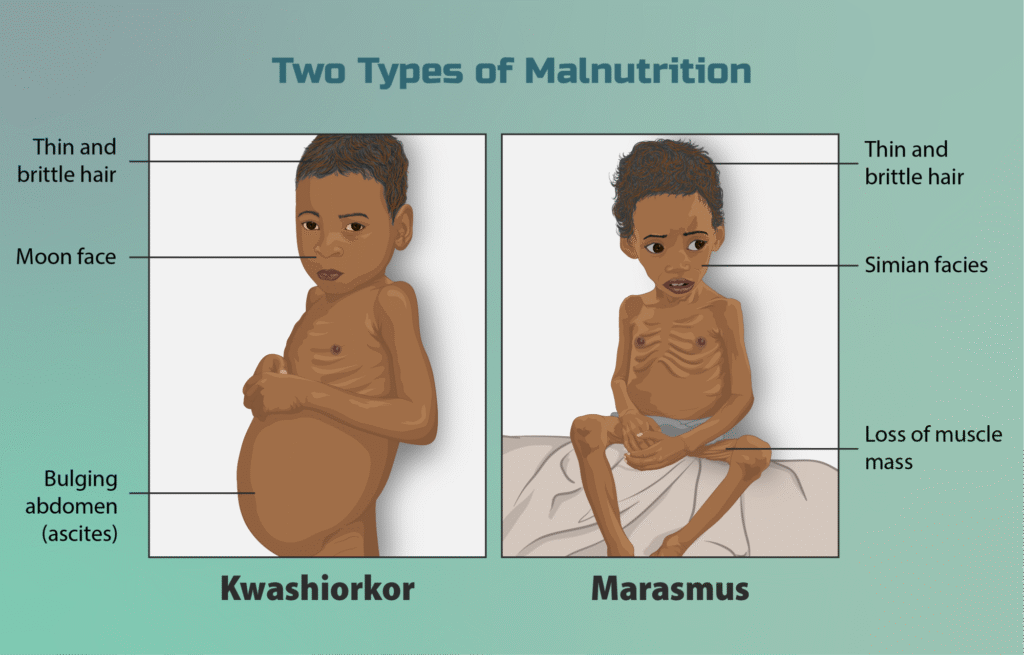

Hunger here shows itself slowly. Some children develop marasmus, losing fat and muscle until the ribs, spine, and joints are visible. Others show signs of kwashiorkor, where a lack of protein causes swelling in the stomach and feet, and hair becomes thin and brittle. Faces can look either hollow or round, and small infections last longer because the body can no longer fight them.

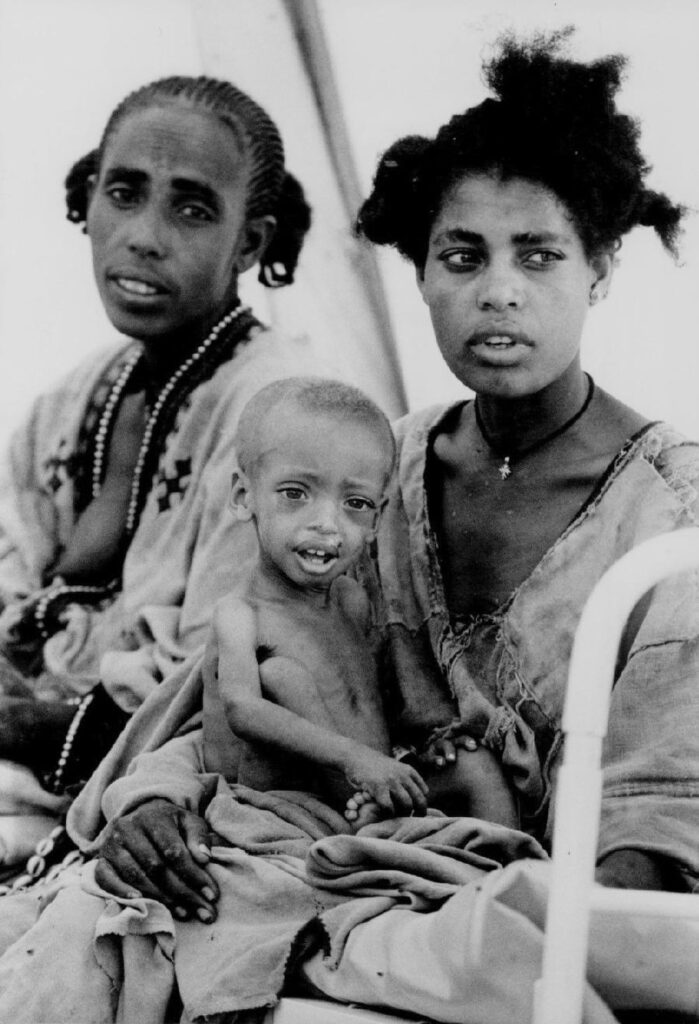

Photo: WikiCommons

The physical effects of hunger progress in stages. At first, people feel tired and cold. Children become quieter. Adults move more slowly. As hunger continues, the body uses stored fat and then begins breaking down muscle. The immune system weakens. Illness lasts longer. Cuts heal slowly. Concentration becomes difficult. Speech decreases. In advanced stages, people become too weak to stand or walk.

Hunger here follows patterns seen before. In Ethiopia, hunger was already taking lives in Wollo in 1973, years before the 1983–1985 famine became widely recognized and claimed more than one million lives. In the Sahel in the early 1970s, rainfall failed across several seasons and hundreds of thousands of people starved as herds collapsed. In North Korea in the 1990s, estimates of famine deaths range from 240,000 to more than one million. In each case, the crisis did not begin when the world declared it a famine. It began quietly as families reduced meals, sold their animals, and grew weaker long before the wider world took notice.

Photo: Ethiopia, 1973, unnamed photographer

In a small refugee post in Ethiopia, a nurse keeps a notebook where she records the weight of each child who comes in. She says the change is seen not in the numbers, but in how slowly children walk to the scale and how long they rest before speaking. Minor fevers now require days of recovery. A cut on a knee may stay open for weeks. Hunger appears as a slow reduction of strength, movement, and healing.

Photo: A severely malnourished child at Hilaweyn health facility. P. Heinlein: Somali Refugees Face Harsh, Uncertain Fate in Ethiopian Camps. VOA News, photo gallery

In Ethiopia and Somalia, some areas have experienced five failed rainy seasons in a row. Soil has hardened. Crops such as sorghum and maize, once reliable, no longer sprout. People wait for rain that does not come. Farmers say the land feels unfamiliar. The climate has shifted into something they do not recognize.

Aid organizations report that assistance is reaching people, but not consistently and not in all areas. Roads are poor, distances are long, and distribution depends on security conditions.

Food prices have increased. Grain that was once affordable now costs more than many families earn in a week. Imported staples have replaced local harvests in many markets. When households cannot grow or buy food, they reduce meals to stretch time. Children become less active. Adults work through dizziness and fatigue. Hunger becomes routine.

Some families leave when conditions become unlivable. They walk to towns or cross borders. Camps form at the edges of roads and settlements. People stay as long as they can, then move again. Displacement is gradual.

Health workers say the hunger they are seeing is not sudden starvation. It is slow deterioration.

Communities adapt with what they have. Families share food when possible. Women organize cooking groups to stretch ingredients. Farmers save seed in case conditions improve.

Governments and international agencies acknowledge the hunger crisis, but the response has not kept pace with reality on the ground. Reports are issued and pledges are made. Implementation is slower. Decisions take time to move through funding channels and logistics systems. Hunger does not pause during this process. It continues in the background, inside households, regardless of planning timelines.

The underlying issues are practical. Roads determine who can reach a market. Water systems determine whether crops can be planted at all. Local agriculture depends on seeds, tools, storage, and transport, not only rain. Governance matters most in remote areas, where basic support arrives last if it arrives at all. Climate change adds pressure by making growing seasons less predictable than they once were. Food security depends on whether this system works across multiple seasons, not just one.

Hunger advances in this slower way. It does not begin with a single event. It develops quietly, far from capital cities and major announcements, until the effects can no longer be ignored.

Although the scale of hunger in the Horn of Africa is large, slow emergencies do not receive the same recognition as sudden violence. The world names a crisis quickly when deaths come fast, such as in war. The Second World War took tens of millions of lives. The genocide in Rwanda killed an estimated eight hundred thousand people within months. The conflict in Syria has taken hundreds of thousands more over the past decade. Yet hunger affecting tens of millions rarely receives the same urgency, because the decline happens quietly, inside households, without a single moment that forces the world to look. The scale is comparable in human impact, but the progression is slower, and therefore easier to overlook.

This is what it means when a crisis is slow. It is present long before the world calls it by its name.

Sources

Featured photo: Turkana, Kenya. Marisol Grandon/Department for International Development

• UNICEF — Horn of Africa Drought Emergency Situation Reports (2022–2024)

• WFP — Food Security and Nutrition Update, Eastern Africa Region

• FAO — East Africa Seasonal Crop and Rangeland Assessments

• UN OCHA — Humanitarian Needs Overview for Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia

• FEWS NET — Food Security Outlook for the Horn of Africa

• Academic famine mortality research:

- Ethiopia 1983–1985 (~1 million+)

- Sahel drought 1968–1974 (several hundred thousand)

- North Korea famine 1990s (240,000 to >1 million range)

- Reuters and AP field reporting on livestock loss, displacement, and price increases

Ethical Disclosure

The nurse account is a composite drawn from multiple interviews and field reports. Names and identifying details have been changed to protect individuals while accurately representing conditions observed.

This article documents how hunger advances slowly in the Horn of Africa and how families experience decline long before the world recognizes a crisis.

Haunting truth.

It is a blessing to look after a child.

Let support children and build their future.

Thank you for your comment. 100%.

thank you for reporting this

…