By FFA News Editorial Desk

In 2013, African leaders made a fifty year promise. They did not whisper it. They announced it at the African Union’s golden jubilee, fifty years after the creation of the Organization of African Unity. The symbolism was deliberate. A second independence. A reset of direction. A declaration that Africa would no longer drift decade to decade without a map.

They called it Agenda 2063.

It was presented as more than policy. It was framed as destiny. A long arc plan to transform Africa into a prosperous, united, self directed global power by the year 2063. The vision was clear. The scale was enormous. The timeline was longer than most political careers, longer than most presidencies, longer than most public memory.

Ten years later, the promise still stands. So do the questions.

Agenda 2063 is not a single project. It is a governing system. A continental blueprint that reaches into national budgets, industrial strategies, trade rules, transport corridors, energy grids, education pipelines, and border controls. It moves through regional economic communities and African Union agencies. In theory, no major national policy on the continent is supposed to contradict it.

In practice, many citizens have never heard of it.

This is one of the central paradoxes of Agenda 2063. It shapes almost everything, while remaining largely invisible to the public.

The plan was born out of failure as much as ambition.

Post independence industrial dreams collapsed under debt. Structural Adjustment Programs stripped public systems and froze state planning. Export economies never escaped raw materials. Youth populations surged without matching employment. Borders remained hard. Infrastructure lagged decades behind growth. Foreign capital began moving faster than African regulation.

By the early 2010s, China, the Gulf States, private equity, and multinational lenders were reshaping Africa at a speed African governments struggled to control. The African Union, newly rebranded from the OAU, needed a continental answer that matched the scale of what was happening.

Agenda 2063 became that answer.

On paper, it affects everyone. Farmers, traders, teachers, energy workers, manufacturers, transport operators, digital entrepreneurs, civil servants, students. Entire ministries realigned around its language. National development plans were rewritten to match its architecture. Infrastructure corridors were fast tracked. Trade integration accelerated.

It is reshaping economies whether people approved it or not.

At its core, Agenda 2063 runs on seven aspirations. A prosperous Africa driven by inclusive growth. A politically integrated continent. Governance rooted in democracy and law. Peace and security. Cultural confidence. People driven development led by women and youth. A continent that competes globally rather than pleading at the margins.

Every law, loan, and megaproject attached to Agenda 2063 claims loyalty to these ideals.

Reality, as always, complicates the promise.

The first ten year phase ran quietly from 2013 to 2023. It was known as the First Ten Year Implementation Plan. It translated vision into targets. Factories, ports, roads, power plants, customs systems, digital platforms. It aligned national budgets, regional blocs, and continental benchmarks.

By the end of that decade, African leaders declared progress. Trade integration moved. Transport corridors expanded. Digital banking platforms exploded. The African Continental Free Trade Area officially entered force.

At the same time, debt ballooned. Informal economies remained dominant. Job creation lagged behind population growth. Power cuts still crippled local industry. Food price shocks repeatedly exposed fragile systems.

The decade built infrastructure faster than it built stability.

Agenda 2063 is now in its second decade. This is the phase where patience runs thinner. Where loans begin maturing. Where industries must prove they can employ millions. Where energy systems must deliver without collapse. Where trade integration must lower prices instead of raising them.

This is where development stops being rhetorical.

Supporters see Agenda 2063 as Africa’s first true attempt at long range self direction. They argue it will finally push the continent beyond exporting raw materials into value added production, digital economies, manufacturing, and intra African trade. They see it as a shield against geopolitical exploitation.

Critics see something else. They see elite capture, rising debt exposure, megaprojects that reward political loyalists, concession contracts that outlast governments, and public disengagement from decisions that reshape entire nations.

Both sides agree on one thing: Agenda 2063 now holds enormous power over Africa’s economic future.

One of the most dangerous weaknesses of the entire framework is public awareness. Most Africans did not vote on Agenda 2063. They did not debate its debt models. They do not track its procurement flows. They do not see its performance dashboards. Yet its consequences shape electricity prices, food transport costs, border delays, employment patterns, and currency risk.

The plan operates far above daily survival, but its failures land directly inside it.

The deeper truth is this.

Agenda 2063 is not just a development plan. It is a power structure. It determines who finances Africa, who builds it, who owns what is built, who profits first, and who absorbs the long tail of risk.

Africa has not lacked vision before. It has lacked protection from capture. Agenda 2063 now sits directly on that fault line.

If it works, Africa shifts from extraction to production.

From debtor to trader.

From fragmented markets to continental power.

If it fails, another generation disappears into policy language without deliverance.

This future is still being negotiated. In loan agreements. In procurement tenders. In border posts. In power grids. In youth employment statistics. In food prices.

Agenda 2063 is not finished but it is unfolding.

And most Africans are still watching from the outside.

The future of Agenda 2063 is not decided in conference halls alone. It is being tested inside specific countries, under very different political pressures, debt loads, and public expectations. The same vision moves through radically unequal terrain.

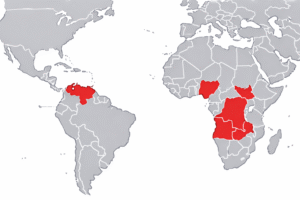

In Rwanda, Agenda 2063 found a government already built for centralized long term planning. Kigali aligned national policy tightly with the AU framework. Infrastructure expansion, digital governance systems, health access, and logistics corridors all moved quickly. Supporters cite Rwanda as proof that disciplined execution can turn continental vision into operational change. Critics point to political control, limited opposition space, and the risks of development without open civic negotiation. Rwanda shows what Agenda 2063 looks like when speed outruns pluralism.

In Kenya, the agenda merged into a fast growing economy already driven by logistics, technology, and regional trade. The Standard Gauge Railway, port expansions, energy projects, and the rise of the digital payments economy all became part of Kenya’s 2063 alignment story. At the same time, debt levels climbed, food prices surged, and youth unemployment stayed stubbornly high. Kenya reflects the tension at the heart of the agenda. Growth without insulation. Integration without full protection.

In Ethiopia, Agenda 2063 collided directly with internal conflict. Massive infrastructure investments, industrial parks, and manufacturing zones once showcased a leap toward Africa’s industrial future. War, displacement, and political fragmentation interrupted that trajectory. Ethiopia became a warning that development frameworks cannot outrun political instability. Vision does not substitute for peace.

In Ghana, Agenda 2063 folded into a democracy that embraces long range planning but remains deeply exposed to currency shocks, food price volatility, and debt restructuring. Ghana adopted trade integration language, manufacturing ambitions, and agricultural modernization under the continental framework. It also became one of the clearest examples of what happens when debt servicing overtakes public spending. Ghana illustrates how easily a reform narrative can be swallowed by macroeconomic reality.

In Morocco, the agenda aligned with a state already oriented toward export manufacturing, renewable energy, and trade integration with Europe and West Africa. The country leaned hard into industrial positioning, logistics corridors, and renewable power. Supporters call it a model of strategic continuity. Critics argue it reveals how Agenda 2063 advantages countries already structurally positioned for global capital.

In South Africa, the vision collided with a slow growth economy, power grid collapse, rising inequality, and mass unemployment. South Africa carries the institutional weight to execute Agenda 2063 but struggles under governance failure. It exposes the central contradiction of the framework. Capacity does not guarantee performance.

Not every country could even attempt alignment.

In Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, the agenda competes with oil dependency, currency instability, insecurity, and fragmented federal governance. Long range continental planning struggles to survive inside daily fiscal firefighting. Nigeria demonstrates how scale alone does not guarantee continental leadership.

In Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea, survival politics leave little room for fifty year vision. Conflict dismantles timelines faster than any development plan can protect them.

Agenda 2063 moves differently in every state because power, debt, institutions, and stability differ profoundly.

Behind the public language of African self direction stands another layer that quietly shapes the agenda: the continental and global institutions that monitor, finance, and audit it.

The African Development Bank plays a central operational role. It funds roads, ports, power plants, transport corridors, digital systems, and industrial infrastructure aligned with Agenda 2063. It publishes progress reports, growth forecasts, and project performance metrics. On paper, the bank positions itself as Africa’s shield against predatory lending. In practice, it still operates inside global capital markets that price risk with little patience for political delays.

The United Nations, through multiple agencies, treats Agenda 2063 as Africa’s counterpart to the global Sustainable Development Goals. UNDP monitors governance. UNECA tracks industrialization and trade. UNICEF and WHO fold human development indicators into the continental vision. The UN does not control Agenda 2063, but it uses it as a template for aid alignment and policy coordination across the continent.

The World Bank and IMF observe the agenda through a more transactional lens. They track fiscal sustainability, debt ratios, currency exposure, and macroeconomic risk as Africa chases long term transformation. Their influence often appears indirectly. When debt becomes unsustainable, policy space shrinks. When currencies collapse, social spending tightens. Agenda 2063 may set fifty year goals, but debt schedules often dictate five year realities.

Together, these institutions act as both enablers and constraints. They help fund the transformation. They also police its financial boundaries. Africa’s development vision does not operate in sovereign isolation. It runs through a tightly surveilled global financial system.

Supporters argue that this oversight ensures discipline. That it prevents waste. That it imposes performance metrics on politics. That it keeps the vision anchored in economic reality.

Critics argue the opposite. That Africa’s future is being built under constant creditor supervision. That continental independence still moves inside externally set risk frameworks. That Agenda 2063 cannot be fully sovereign as long as financing remains dependent on institutions that answer to shareholders outside the continent.

This is the unresolved tension inside the entire project. Africa is told to dream in fifty year arcs while borrowing on five year cycles.

What happens next will not be decided by slogans.

The second ten year phase will test whether industry can absorb Africa’s youth at scale. Whether power grids can stabilize. Whether intra African trade lowers prices instead of raising them. Whether farmers gain protection or lose markets. Whether women led enterprises receive capital or remain symbolic. Whether digital economies produce formal employment or only platform dependency.

It will also test whether governments are willing to make the public an actual participant in the plan that governs their future.

Agenda 2063 does not fail quietly. It fails publicly. In blackouts. In currency crashes. In youth unrest. In food price riots. In border bottlenecks.

Or it succeeds visibly. In jobs. In exports. In industrial supply chains. In income stability. In food security. At its core, this is the wager.

Africa planned its future in fifty year increments.

Its people live inside weekly uncertainty.

Bridging that distance is not a technical challenge. It is a political one.

Sources

African Union Commission. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want – Framework Document. 2015. AU. PDF. archive.uneca.org+1

African Union Commission. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want – Popular Version. April 2015. AU. PDF. au.int+1

African Union Commission. “Goals & Priority Areas of Agenda 2063.” Accessed via AU website. au.int+1

African Union Commission. Report of the Commission on the African Union Agenda 2063. Assembly Report, Addis Ababa, January 2015. portal.africa-union.org

African Union Commission et al. 2024 Africa Sustainable Development Report: Reinforcing the 2030 Agenda and Agenda 2063. UNDP / AfDB / AU / ECA. 2024. PDF. UNDP

United Nations / AfDB / AU. Annual Africa Sustainable Development Report (various years) — e.g. 2017 report reviewing SDGs and Agenda 2063 progress.