Could the forces now reshaping Venezuela’s future one day confront Africa’s resource-rich economies as well?

That question moved closer to the surface this week after U.S. officials announced that President Nicolás Maduro had been detained following long-standing criminal charges, alongside a declaration that Washington would assume oversight of Venezuelan oil exports under a new framework. International news outlets reported immediate uncertainty across energy markets, reflecting concerns over production, investment, and control of one of the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

U.S. authorities say the action is rooted in legal proceedings and national security concerns. Critics, including several foreign governments and analysts, argue the move cannot be separated from Venezuela’s oil wealth and strategic value at a time of tightening global energy supply.

Both perspectives are documented. What is less debated is what such moments have historically meant for food security and everyday life in resource-dependent nations.

Hunger risk in Venezuela

Venezuela is already experiencing widespread food insecurity. United Nations agencies and humanitarian organizations estimate that roughly one third of the population faces moderate to severe food insecurity, with child malnutrition persisting in low-income urban neighborhoods and rural regions. Even where food is available, affordability remains a central barrier as purchasing power has eroded.

For years, oil revenues financed food imports, healthcare, and social programs. As imports expanded, domestic agricultural production declined. When sanctions, currency collapse, and political conflict converged, the import-dependent food system proved fragile.

Aid workers and regional NGOs have repeatedly noted that food access deteriorated well before recent developments. The current shift in oil governance adds another layer of risk. Any disruption to export revenues, currency stability, or trade logistics directly affects food prices, transport costs, fertilizer access, and ultimately household diets.

Venezuela’s hunger crisis did not begin with empty shelves. It began with weakened trade capacity and declining purchasing power.

A pattern older than modern geopolitics

Observers pointing to resource-driven pressure often reference a much longer historical record.

In antiquity, the Roman Empire expanded into North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean to secure grain and mineral supply. European colonial powers later fought over gold, rubber, spices, and oil across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In the modern era, interventions in Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan have been officially justified on security, governance, or legal grounds, while strategic resources shaped long-term economic outcomes.

Foreign interventions are rarely framed explicitly around resource acquisition. Official rationales consistently emphasize security threats, terrorism, or legal violations. Still, analysts across energy, economic, and foreign-policy disciplines note how frequently strategic resources are present in countries experiencing prolonged external pressure.

Correlation does not establish motive. The economic consequences, however, are observable.

Why food systems fail first

Oil and minerals are globally traded commodities priced largely in foreign currency, most often the U.S. dollar. Countries that rely heavily on these exports also tend to import a significant share of their food.

When export revenues fall or become restricted, currencies weaken. As currencies weaken, food prices rise. Transport costs increase. Fertilizer becomes more expensive. Imports slow or stall. Hunger emerges gradually, then abruptly.

Multiple economic studies confirm that resource-dependent economies with high food import reliance face elevated food insecurity during external shocks, including sanctions, conflict, and price volatility.

Venezuela is not unique

Venezuela’s experience mirrors patterns seen elsewhere.

In Iraq, repeated disruptions to oil production following the 2003 invasion contributed to inflation and long-term dependence on food imports. Libya’s 2011 conflict fractured oil output and destabilized national food distribution networks. Afghanistan, despite vast untapped mineral wealth, remained heavily reliant on imported food throughout decades of intervention and instability.

Political contexts differ. The economic mechanics are strikingly similar.

Africa’s exposure

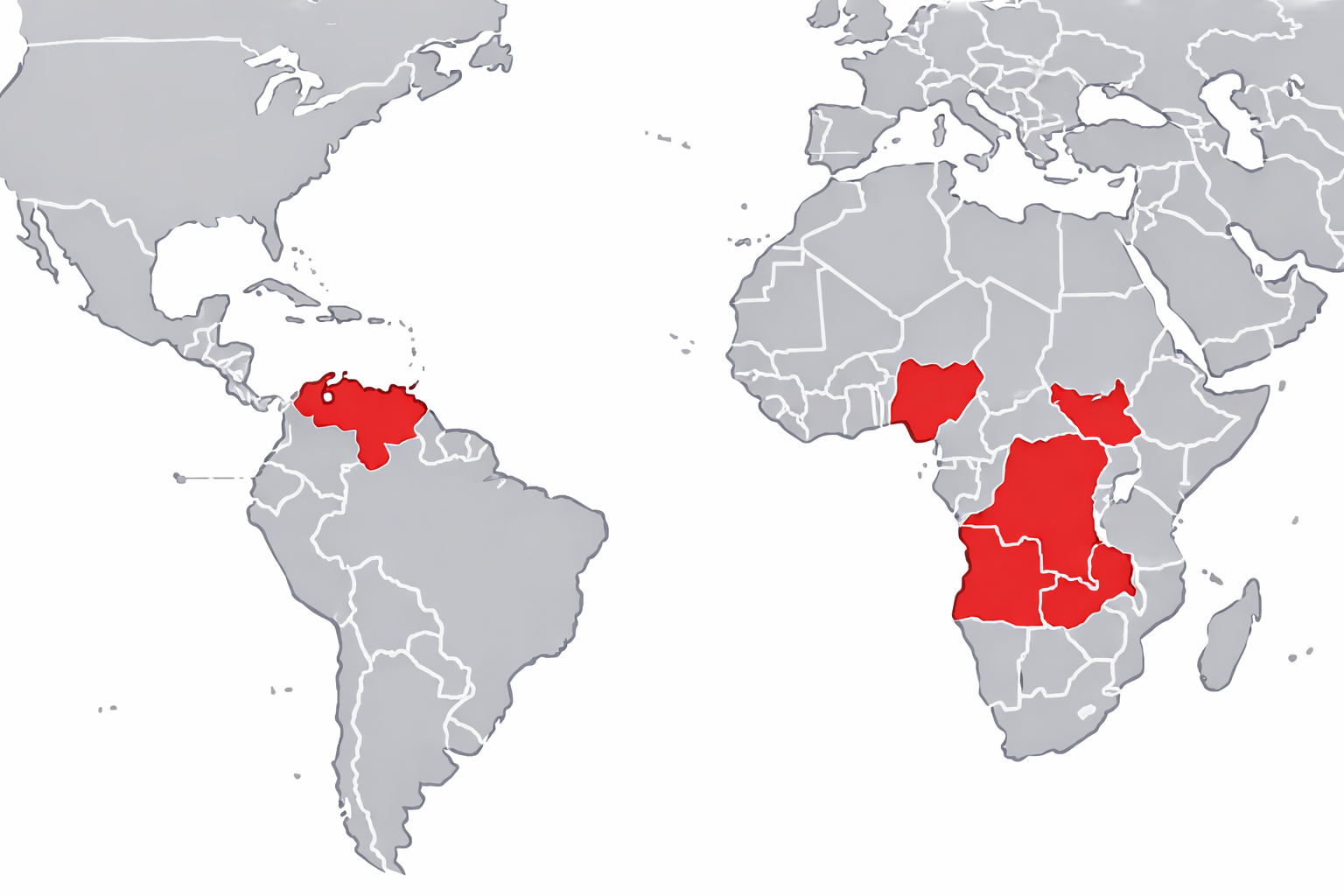

Africa holds substantial oil and mineral reserves essential to global supply chains, from Nigerian crude to Congolese cobalt.

Several African countries share structural traits with Venezuela at earlier stages: export concentration, currency sensitivity, and food import dependence.

Nigeria and Angola export energy while importing large portions of staple foods. Democratic Republic of the Congo supplies minerals critical to global manufacturing while facing conflict and infrastructure gaps. Zambia depends heavily on copper revenues, with food prices rising when global demand softens and the currency weakens.

This does not mean Africa is destined to repeat Venezuela’s trajectory. Political systems, demographics, and regional cooperation differ substantially. But the exposure is real. Countries with diversified economies, strong domestic food production, transparent resource contracts, and regional trade buffers absorb shocks more effectively. Those dependent on a narrow export base and imported food remain vulnerable.

The broader lesson

Venezuela’s crisis is still unfolding, and its long-term outcome remains uncertain. What history already demonstrates is that resource wealth alone does not guarantee stability. In some cases, it amplifies vulnerability when global power competition intensifies.

For Africa’s resource-rich nations, the central question is not whether oil and minerals bring opportunity. It is whether food systems are resilient enough to withstand what comes when markets shift, pressure rises, and external interests move closer.

In Venezuela, the consequences are already visible in food prices, nutrition data, and migration flows. Hunger is rarely the headline at the start of a geopolitical crisis.

It is usually the receipt.

Sources

Al Jazeera. “U.S. to Dictate Decisions on Venezuela, Control Oil Sales Indefinitely.” Al Jazeera, January 8, 2026.

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2026/1/8/live-us-to-dictate-decisions-to-venezuela-control-oil-sales-indefinitel

Associated Press. “Venezuela Live Updates as U.S. Details Actions Following Maduro Detention.” AP News, January 2026.

https://apnews.com

BBC News. “Venezuela Crisis Explained: Oil, Sanctions, and the Economy.” BBC News.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-48121148

Council on Foreign Relations. “Venezuela in Crisis.” Council on Foreign Relations.

https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/venezuela-crisis

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Africa’s Growing Food Import Bill. Rome: FAO.

https://www.fao.org/4/i2497e/i2497e00.pdf

Financial Times. “Oil Prices Fall as Uncertainty Grows Over Venezuela’s Energy Sector.” Financial Times, January 2026.

https://www.ft.com

International Fund for Agricultural Development. “Angola: Rural Development and Natural Resources.” IFAD.

https://www.ifad.org/en/w/countries/angola

International Monetary Fund. “Venezuela: Country Data and Economic Indicators.” IMF.

https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/VEN

Reuters. “U.S. Wants Venezuelan Oil Flowing Again, With Revenues Managed Under New Framework.” Reuters, January 7, 2026.

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-wants-venezuelan-oil-flowing-again-with-revenues-us-accounts-wright-says-2026-01-07/

Reuters. “U.S.–Venezuela Oil Deal Pushes Prices Lower, Draws International Criticism.” Reuters, January 7, 2026.

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-venezuela-oil-deal-angers-china-pushes-prices-down-2026-01-07/

The Guardian. “U.S. Claims Long-Term Oversight of Venezuela’s Oil After Maduro Detention.” The Guardian, January 8, 2026.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/08/venezuela-oil-deal-rodriguez-trump-vance-claims-us-control

World Bank. Africa’s Pulse: Economic Update. Washington, DC: World Bank.

https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/publication/africas-pulse