At first light in Konso, southern Ethiopia, Samrawit fills a yellow jerrycan and joins the line. The borehole is closer than last year, but the queue still eats her morning. If the pump stalls, she will walk farther. If the rains fail, she will walk longer. By the time she reaches school, the first lesson is over. UNICEF

Across Ethiopia, water is carried on heads and backs. The price is hours. In households without water on the premises, women and girls do most of the fetching in the vast majority of homes. A single round trip often takes 30 to 60 minutes, and in many rural kebeles it stretches beyond an hour, especially in the dry season. Those minutes come out of study time, work time, and rest. UNICEF DATAWorld Bank

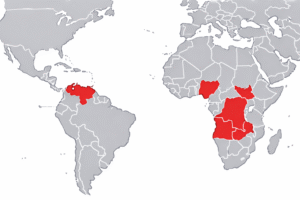

Season decides the route. When rains are poor, nearby springs and shallow wells dry up and families push to farther sources. When rains arrive, flooded paths slow the walk and queues grow. New analysis across Sub-Saharan Africa finds that more precipitation is linked to shorter fetching times. About one centimeter more weekly rain over the past year reduces walking time by roughly three and a half minutes. Drought does the opposite. NatureIDEAS/RePEc

Schooling bears the cost. Evidence from Ethiopia shows girls miss class to help collect water. Where schools add reliable WASH and menstrual hygiene facilities, attendance improves, especially for adolescent girls. This plays out at scale too. In 2023, an estimated 447 million children worldwide attended schools without a basic drinking water service, a quiet driver of absence that keeps days short and futures smaller. PMCWorld BankUNICEF DATA

There is progress. Ethiopia is expanding rural groundwater systems in drought-prone areas, connecting communities that once relied on seasonal sources. In Adami Tesso and Kumato, new piped schemes now serve more than 24,000 people, giving families back time that used to be spent walking for unsafe water. Every minute saved at the source reappears in a classroom, a shop, or a field. World Bank

Time is the currency that never shows up in budgets. Bringing water closer, keeping pumps working year-round, and publishing simple local service data can buy that time back quickly. In places like Konso, you can measure the return in first-period lessons attended and in girls who arrive before the bell.

Featured image attribution: Shafiq Kayondo, CC BY-SA 4.0Sources and further reading

- WHO and UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme, 2023 household WASH update with gender focus. Women and girls are the primary water collectors in most households without on-premises water. https://data.unicef.org/resources/jmp-report-2023/ UNICEF DATA

- World Bank interactive, 2024. Typical fetching durations in Sub-Saharan Africa frequently run 30 to 60 minutes per trip, and longer in many settings. https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2024/03/13/gendered-burden-of-water-collection-in-afe-afw-sub-saharan-africa World Bank

- Nature Communications, 2025. More precipitation shortens walking times; about 3.5 minutes less per 1 cm increase in weekly rainfall. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-58780-9 Nature

- UNICEF Ethiopia, 2024. Water system restorations in conflict-affected areas reduce time burdens and help girls stay in school. https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/stories/water-matters-girls-their-education-their-future UNICEF

- World Bank feature, 2025. Rural groundwater resilience program connecting communities to safe piped water in Ethiopia. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2025/05/22/strengthening-water-resilience-in-ethiopia-s-rural-communities-afe World Bank

- UNICEF and WHO, JMP WASH in schools, 2024 update. 447 million children without a basic drinking water service at school in 2023. https://data.unicef.org/resources/jmp-wash-in-schools-2024/ UNICEF DATA

- Research on Ethiopia: Girls miss school due to water collection; adding WASH facilities improves attendance. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5719478/ and https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-024-03558-xPMCbmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com