Them get money for war. No time for the poor.

It began as a short comment under an article on Food for Africa News. The article was titled, “The World Counts Wars in Days and Hunger in Decades.” A reader named Kofi replied on Facebook, with a simple line: “Them get money for war. No time for the poor.”

Those words raise a serious question. Why do governments find money for weapons, but struggle to find money for food? How many lives are lost in wars, and how many are lost to hunger? And who gains, while so many lose?

Spending on War

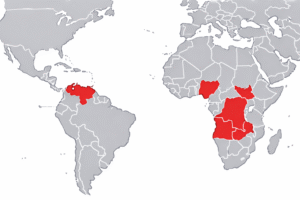

In 2024, the world spent about 2.7 trillion dollars on militaries. That was the highest ever, and it was 9 percent more than the year before. Military budgets have risen every year for the past ten years. Today, they make up about 2.5 percent of the world’s entire economy.

The United States alone spent close to 1 trillion dollars in 2024. That was more than one-third of all global military spending. Other countries in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East also raised their defense budgets.

Photo attribution: Davidsvine, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Cost of Ending Hunger

The money needed to fight hunger is much smaller. Oxfam estimates that about 31 billion dollars each year could cover the main needs to reduce hunger worldwide. The World Food Programme says that about 40 billion dollars per year, could end hunger by 2030.

Photo attribution: Okello warom, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

One aid group explained it this way: the world spends so much on weapons that just one day of global military spendingwould cover the emergency food aid needed to save millions.

Yet hunger remains deadly. Each year, about 9 million people die from hunger and related causes. That means hunger kills far more people than wars do.

War and Hunger Together

War kills directly, but it also fuels hunger. In 2019, about 80,000 people died from armed conflicts. By comparison, hunger and malnutrition killed millions. But in war zones, the two combine: about 60 percent of hungry people in the world live in conflict areas.

Photo attribution: Jaber Jehad Badwan, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

When fighting breaks out, farms are abandoned, roads are blocked, markets are destroyed, and food becomes a weapon. In recent years, wars in Sudan, Yemen, and Gaza have all pushed millions to the edge of famine. During the post-9/11 wars, researchers estimate that almost 5 million people died, not only from violence, but from hunger, disease, and collapse of health systems linked to war.

Who Gains, Who Loses

Governments often justify large military budgets as necessary for national security. The defense industry benefits through steady contracts and long-term procurement, which keeps funding locked into the system year after year.

By contrast, hunger relief does not have long-term, guaranteed funding. Most famine and food aid programs are supported by short-term appeals and voluntary donations. This means that when a crisis strikes, money has to be raised again, and the delay often costs lives.

The poor pay the price. Families are displaced, food becomes too costly, children suffer malnutrition, and health systems break down. In some cases, food itself is blocked or stolen, used as a tool in the conflict.

What Is Being Done

Some groups and campaigns are calling for change. Oxfam says that if wealthy countries moved even 3 percent of their military budgets to hunger and debt relief, it could make a major difference. Other proposals suggest a “peace dividend,” where nations reduce military budgets by just a few percent each year and use the savings for food, health, and education.

There are also efforts to make aid more effective. Humanitarian groups push for safe corridors to deliver food during fighting, and for programs that support farmers directly rather than only bringing in imported food.

Still, the barriers are large. Governments see cutting military budgets as risky. Corruption and weak institutions often block food aid from reaching the people who need it. And in war zones, access to food and water is often denied by force.

What More Could Be Done

The numbers show that even small changes could help. One percent of global military spending would more than cover the cost of ending hunger. Redirecting parts of budgets, tying military spending to social spending, and investing in local farming systems would all build resilience.

Most importantly, peace itself is a hunger solution. Ending wars, preventing conflicts, and investing in stability could cut both the direct and indirect causes of hunger.

A Question for Readers

Kofi’s comment, “Them get money for war. No time for the poor.” points to a truth in these numbers. The world finds trillions for weapons, while millions still go hungry.

But, this does not have to be an either-or choice. Nations may keep armies, but can they not also spare enough to ensure that no child dies for lack of food? The choice is not only for leaders. It is also for the public, whose voices can shape what is valued most.

Sources

- Food for Africa News, Official Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/19yCs84s1o/

- “The World Counts Wars in Days and Hunger in Decades” article: https://foodforafrica.news/the-world-counts-wars-in-days-and-hunger-in-decades/

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI): Trends in World Military Expenditure 2024

- SIPRI Press Release: Global military expenditure rises by 9.4 percent in 2024

- Oxfam: Less than 3% of G7 military spending could help end global hunger

- World Food Programme USA: How much would it cost to end world hunger?

- Concern Worldwide: World Hunger Facts

- Our World in Data: War and Peace

- Brown University Costs of War Project: Civilian deaths and displacement

- Oxfam: One person dying of hunger every four seconds