ABUJA, Nigeria – The Federal Government has urged African leaders to take full ownership of the fight against malaria. At the “Big Push” meeting in Abuja, Coordinating Minister of Health Professor Muhammad Ali Pate said: “Malaria is not someone else’s problem; it is our problem. Ninety percent of the global burden is here in Africa. Unless we own it, fund it, and act decisively, we will be back here next year and the year after, repeating the same conversations” (Fed Min of Info & Nat’l Orien, 14 Sept 2025).

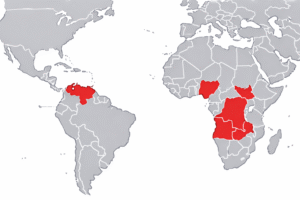

This call comes as Africa still bears the heaviest burden of malaria, with 263 million cases and nearly 600,000 deaths recorded worldwide in 2023, 95 percent of them in Africa (WHO, 2023).

But malaria does not stand alone. It is part of a dangerous triangle: malaria, dirty drinking water, and hunger.

Dirty Water and Malaria

Malaria is spread by mosquitoes that breed in stagnant and polluted water. Poor sanitation means more standing water around homes, which creates breeding grounds. Studies show that children in households without safe drinking water or sanitation are at higher risk of malaria infection (Yang et al., 2019). The same unsafe water also exposes families to diarrheal disease. Communities end up fighting two health battles at once.

Photo attribution: USAID, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hunger and Malaria

Hunger and malnutrition make malaria deadlier. Malnourished children are less able to fight infection. Research shows that stunting, wasting, and underweight children face higher risk of both catching malaria and dying from it (Das et al., 2018). At the same time, when malaria strikes during the “hunger season” before harvest, families lose both food security and income. It becomes a vicious cycle.

Photo attribution: DFID – UK Department for International Development, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A Triangle

Africa cannot treat malaria as an isolated problem. As Professor Pate said, “Nearly one-third of visits to our hospitals are due to malaria or its complications.” But the conditions that drive malaria—dirty water and hunger—are equally urgent. If we continue to fight malaria without tackling water and food, the cycle will repeat.

A new way of thinking is needed: malaria control must be tied to safe water and food security programs. Imagine if every mosquito net campaign also included investment in drainage and clean water. Imagine if malaria prevention went hand in hand with child nutrition programs. Addressing the triangle together would break the cycle that keeps Africa sick and hungry.

Moving Forward

Nigeria’s move to localize malaria solutions: producing test kits and bed nets at home, and integrating care into primary health systems is a step in the right direction. But Africa must go further.

Malaria is preventable and treatable. Yet its impact becomes far worse in places where families face food shortages and children are malnourished, and where unsafe water and poor sanitation create more breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Though these conditions do not cause malaria, they multiply its toll and make control efforts harder.

To defeat malaria, Africa must fight it on all fronts: disease, water, and hunger because they go hand in hand.

Sources

- Fed Min of Info & Nat’l Orien, Nigeria. (14 Sept 2025). Press release on “Big Push” to end malaria.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). World Malaria Report.

- Yang, D. et al. (2019). Drinking water and sanitation conditions are associated with the risk of malaria among children under five years old in sub-Saharan Africa. PubMed.

- Das, D. et al. (2018). Complex interactions between malaria and malnutrition. BMC Medicine.