Ghana, West Africa-Kwame sits on land his family has farmed for generations in Ghana’s Bono Region. The soil is rich, the rains steady, and the potential enormous. But while Kwame dreams of turning his fields into a larger business that could feed not only his village but whole districts, he has no idea where to begin. Banks demand collateral he doesn’t have, government schemes feel distant and complex, and private investors rarely look his way.

His story is not unique. Across Africa, fertile land sits idle or underused—not for lack of will, but for lack of opportunity and support.

Food Prices Rising, But Hunger Persists

This month, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported that global food prices edged up in July. The FAO Food Price Index averaged 130.1 points, up 1.6 percent from June, driven mainly by higher costs for vegetable oil and meat. Palm oil, soy, and sunflower oil reached a three-year high, while beef and lamb prices climbed to record levels.

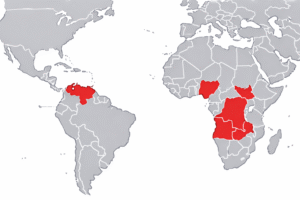

But for farmers like Kwame, and for millions of families across Africa, these global numbers mean little. Even when world prices fall, many African households still cannot put food on the table. According to the UN’s State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025 report, over 307 million Africans—more than 20 percent of the continent’s population—faced hunger in 2024. In West and Central Africa alone, 52 million people are projected to struggle with acute food insecurity during the lean season this year.

Photo: Fanti Salms, CC BY-SA 4.0

When Food Doesn’t Reach the People

Why does hunger persist even when food is available? Part of the answer lies in broken systems.

In Nigeria, dollar shortages make it difficult for importers to pay for grain, trapping food at ports. In Kenya, long queues at Mombasa’s docks mean shipments of wheat and rice can sit for weeks. In South Sudan, poor roads turn a two-day trip into a two-week struggle, and by the time food arrives, prices have doubled.

It isn’t always about the cost of food—it’s about moving it, storing it, and paying for it.

Governments Are Trying, But More Is Needed

Some governments are making efforts. Ghana has expanded its Planting for Food and Jobs program to supply subsidized fertilizer and seeds. Kenya recently opened new grain storage facilities to cut post-harvest losses. Ethiopia is investing in irrigation to reduce dependency on unpredictable rains.

These are positive steps, but they remain small compared to the scale of the problem. Meanwhile, corruption, lack of rural education, weak financial systems, and limited labor training continue to block progress. Farmers like Kwame remain stuck, knowing their land could grow more but lacking the tools and capital to make it happen.

Africa’s Untapped Power

Africa holds 60 percent of the world’s unused arable land. It could feed itself, and much of the world besides. But without serious investment—clean financing, infrastructure, agricultural education, and governance that works—the continent’s potential remains locked away.

Global food prices will continue to rise and fall. But the deeper question is whether Africa will finally invest in its own farmers, like Kwame, who sit on fertile land yet cannot break through the barriers of a disorganized system. Until then, hunger will remain less about scarcity and more about inequality.

Sources

- FAO – “FAO Food Price Index edges up in July” (8 August 2025)

Read here (FAO) - SOFI 2025 – The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025

Read here (WHO / UN Press Release) - WFP – “WFP warns of deepening hunger in West and Central Africa” (2025 lean season)

Read here (Reuters summary of WFP report) - OCHA – Global Humanitarian Overview (2025)

Read here (World Bank PDF citing OCHA data) - Feature photo attribution: Adam Jones from Kelowna, BC, Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0