It is a question that cannot be answered by numbers alone, though the numbers are striking. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has long noted that Africa holds more than 60% of the world’s uncultivated arable land.(1) Yet, according to the World Food Programme (WFP), over 280 million Africans faced hunger in 2024, nearly one in five people.(2) These figures should not exist side by side, yet they do.

Behind those numbers stands the story of Ibriham, a 22-year-old in Mityana, Uganda. His father, along with many other parents in the village, was killed in a bus accident after a wedding. Overnight, households collapsed into grief and scarcity. With no formal protection to safeguard the families left behind, Ibriham found himself guardian of twenty orphans.

The land around him is fertile. Green hills could grow maize, beans, and bananas enough to sustain many. Yet land alone does not make food. There are no ready seeds, little knowledge, and almost no extension services to guide those left behind. Without these, families remain at the mercy of both the soil and fate.

The irony is sharp. Africa exports the very crops that line the tables of Europe, America, and Asia. Cocoa from Ghana and Ivory Coast, tea from Kenya, coffee from Ethiopia. These are household goods abroad. Yet in the villages where they are grown, children go to bed with empty stomachs. Africa feeds the world. But who feeds Africa?

There are models of hope. Kenya’s farmer field schools have taught communities low-cost methods to boost yields, from crop rotation to soil management.(3) Ghana has piloted e-agriculture platforms, sending farmers weather and market information by simple text messages, helping them avoid losses.(4) Malawi has built community grain reserves that act as lifelines during lean seasons.(5) UNICEF and FAO report that such localized interventions reduce child malnutrition significantly when paired with school-feeding programs.(6) These examples prove that solutions are neither grand nor distant, but rooted in local training, shared resources, and protection against shocks.

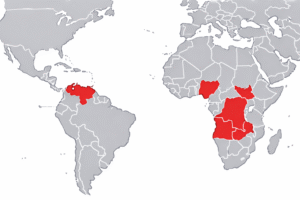

Yet more must be said. Businesses that come to Africa to grow crops, to mine minerals, to hire cheap labor, and to export profits, cannot stand apart from the hunger that surrounds them. If they reap wealth from the soil and the sweat of communities, then it must be their duty to invest in those same communities. This is no longer only moral suggestion; it is becoming law. Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa have moved to strengthen corporate social responsibility frameworks, requiring foreign investors to contribute to local development.(7) Across the continent, governments are drafting regulations that tie business licenses to commitments in education, health, and food security.

Programs are beginning to show what is possible. In Rwanda, agribusinesses partnering under the Sustainable Food Systems initiative have funded farmer cooperatives, providing both training and market access.(8) In Ethiopia, companies operating in the coffee sector are now required to contribute to local health and sanitation projects as part of export agreements.(9) These are steps toward balancing the scales: if Africa’s fields can feed the world, then those who profit must also ensure that Africa’s children eat.

The story of Ibriham and the twenty orphans in Mityana is not isolated. It is a mirror to the larger question. Hunger in Africa is not a failure of soil. It is a failure of systems; of protection for families, of education for farmers, of accountability for businesses that take more than they return.

Thirty years ago, a reflection like this would end with a plea to conscience. The same plea is needed now. Hunger is not merely an empty bowl. It is the absence of justice, of foresight, of the duty owed by neighbor to neighbor and by industry to community. Until these duties are carried, the contradiction will remain: that Africa, so rich in land and labor, feeds the world, while its own children wait for supper.

The question lingers, unresolved yet urgent: Africa feeds the world. But who feeds Africa?

By Janica Southwick, Founder & Editor, Food for Africa News

References

(1) African Development Bank – Feed Africa Strategy: “Africa has 65% of the world’s remaining uncultivated arable land.”

(2) World Food Programme / UN – SOFI 2025 summary: “The proportion of the population facing hunger in Africa surpassed 20 percent in 2024, affecting 307 million people.”

(3) FAO – Review of Farmer Field Schools: Evidence Report.

(4) Innovations for Poverty Action: Text-message weather alerts for farmers in Ghana (Ignitia study).

(5) Government of Malawi – Food Security Action Plan (includes establishment of community grain banks).

(6) FAO – Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition in Africa 2023 (covers school feeding & nutrition).

UNICEF ESA – Food Systems for Children, 2025.

(7) ICLG – Environmental, Social, and Governance Law: Ghana (2025 update).

Parliament of Ghana – CSR policy and framework.

(8) FAO – Rwanda’s journey towards sustainable food systems.

UN Food Systems National Dialogues – Rwanda Report.

(9) Ethiopia Ministry of Mines – Community engagement obligations for licensees.

Capital Ethiopia – Ethiopia raises capital requirements for coffee exporters (2025).