In Chad, hunger has never meant only empty fields. Sometimes the fields are full, and then they are wiped bare by locusts.

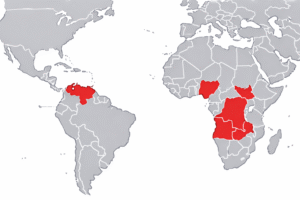

Between 1987 and 1989, the country faced one of its worst infestations. At the time, Chad was the poorest nation in the world. Crops were in the ground, yet starvation was at its peak. Why? Because locusts had become uncontrollable.Desert and migratory locust swarms would sweep in, darkening the skies in broad daylight. According to the World Bank, a swarm just one square kilometer in size could destroy as much food in a single day as 35,000 people ate.

(World Bank – The Locust Crisis: The World Bank’s Response, 2020)

In reaction, the U.S. mission in N’Djamena declared an emergency and called in experts, pesticides, and aircraft. One of those sent was Alfred M. Rivas (1930–2002), a US government entomologist assigned to coordinate aerial spraying. His wife, Gloria, had been expected to accompany him, but he insisted on going first to see if it was safe. It was not.

The conditions were harsh. The heat was extreme, food was scarce, and the swarms blocked out the sun. Rivas lost ten kilograms in just a few months. He had already been a thin man, and he returned thinner still. He gave away his food, all of his clothing, other than the suit on his back, coming back with little more than the suit he wore.

Plenty, Yet Still Hungry

Chad remains one of the most food-insecure countries in the world. More than half of the population is food insecure each year. And yet the country has arable land and resilient farming communities. The problem is not only production, but loss.

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, between 30 and 40 percent of food is lost after harvest due to poor storage, weak infrastructure, and pests. In Chad, millet often spoils before it reaches market. Tomatoes rot on the roadside while trucks fail to arrive. And when locusts hatch in the Sahel, whole communities lose their crops (and their hope) in one season.

When the Harvest Disappeared

Moussa, a farmer near Abéché, depends on sorghum and groundnuts. When locusts arrived one year, he and his neighbors tried everything: banging tins, lighting fires, waving cloth to drive them off. By morning, the fields were bare. “I watched my children starve before my eyes,” he said. Aid came. But it was late. It was long after the hunger had already begun.

The Work in 1987–1989

During the 1987–1989 campaign, Rivas and his colleagues helped carry out aerial spraying missions that saved thousands of hectares. Mortality rates in treated zones reached as high as 95 percent. Villagers described the planes overhead not as foreign machines, but as lifelines.

Rivas gave more than his technical skills. He gave until he had nothing left. He worked alongside the people he served, believing that science without humanity meant little.

Have We Improved?

Today, Chad still faces the same enemies: drought, locusts, and wasted harvests. Nearly 2 million people are projected to be acutely food insecure in 2025 (IPC). Technology has advanced: satellites, drones, pesticides but food still fails to reach the people who need it most.

This raises the question: what has really changed? Reports are written, projects are piloted, yet families continue to live the same reality.

Perspective

When we talk about “first world problems,” it is worth remembering the contrast. In Chad, the problem is not slow internet or a late delivery. It is a harvest eaten overnight. It is a child left with an empty bowl.

This editorial is dedicated to Alfred M. Rivas (1930–2002), my grandfather and to my grandmother, Gloria Rivas (1932-2012), who supported him during his mission. Their work connects to the ongoing struggle of Chad’s farmers, who continue to fight to protect their harvest.

By Janica Southwick | Food for Africa News

Sources

World Food Programme (WFP). Chad Country Brief – Food Insecurity and Vulnerability.

https://www.wfp.org/countries/chad

OTA (Office of Technology Assessment). A Plague of Locusts: Responding to the West African Grasshopper and Locust Invasions. U.S. Congress, June 1990.

https://ota.fas.org/reports/9001.pdf

OTA (Office of Technology Assessment). Chapter 5: What Is the Problem? in A Plague of Locusts, 1990.

https://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk2/1990/9001/900105.PDF

USAID. Technical Cooperation Program: Agriculture and Rural Development. Report, 1980s.

https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PCAAA373.pdf

World Bank. Chad: Agricultural Services and Producer Organizations Project – Implementation Completion and Results Report (2004–2011). Published 2012.

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/273171467990383167/pdf/ICR15530P092570IC0disclosed01090120.pdf